OPDP’s Social Science Research Program: Aiming to Understand How Health Care Providers and Patients Interpret Prescription Drug Information

CDER’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP)’s four-person research team investigates issues in direct-to-consumer and health care provider-directed prescription drug promotional communications. The team uses methodologies such as surveys, experimental research, and qualitative research in their endeavors.

The team also provides technical assistance within FDA and to stakeholders, as appropriate, on the design and implementation of studies concerning prescription drug promotion. The team’s brochure explains the work in more depth.

In this CDER Conversation, we speak to Kathryn (Kit) Aikin, PhD, senior social science analyst and research team lead in OPDP, about this important work.

What is social science research in the OPDP context?

To define social science research in the context of OPDP, it’s important to understand the OPDP mission. This mission is to protect public health by helping to ensure prescription drug information is truthful, balanced, and accurately communicated. OPDP, one of two offices in CDER’s Office of Medical Policy (OMP) super office, guards against false or misleading promotion and helps to make sure that communications about prescription drugs, such as labeling and advertising, empower patients and health care providers to make informed decisions about treatments.

Our social science team investigates how health care providers and patients perceive medical product information, specifically information about prescription drugs, and make subsequent treatment decisions. We look at how different promotional communications affect understanding of the benefits and risks of prescription drugs. Using social science principles, our research identifies barriers that may prevent people from fully grasping the drug’s benefit-risk profile. Equally important, we work to find potential solutions to these barriers. We are very interested in addressing health disparities. To that end, we conduct research on how different consumers’ literacy, education level, age, and other demographical information may affect how they interpret medical information.

How do you come up with your study ideas? How many studies are you working on at any given time?

As you might imagine, this process involves a lot of people! We consider the emerging issues in the field and whether there is a need to follow-up on prior research. We solicit ideas from our OPDP colleagues, OPDP and OMP leadership, and from others in the agency. Feedback from outside groups can be really helpful, too. In November 2021, we hosted a workshop with Duke Margolis, Informing and Refining the Prescription Drug Promotion Research Agenda, where academics shared their research and perspectives.

Once we have finalized our list of proposed studies for a year, we begin writing up proposals. Then we do a lot of internal, behind-the-scenes works to start these studies, like defining the project’s scope and drafting task orders. We generally start four to six new studies every year, and each study runs three to five years. This means we generally have about 20 studies in various stages of progress during a year. Our webpage lists our completed studies, those in progress, and those that are pending peer review and publication.

What have been recent interesting research findings?

One recent project involved patients’ understanding of oncology clinical endpoints that measure a clinical benefit, such as overall survival. Based on a literature review of relevant articles and abstracts, we found that health care providers and patients with cancer generally do not discuss clinical endpoint concepts. As a result, patients can be confused about the purpose of a particular treatment.

We followed up with a series of focus groups, or small group interviews. In these interviews, we asked 36 survivors of cancer and 36 adults in the general population about oncology clinical endpoints. Again, few participants were familiar with the term. We are now starting to set up an experimental study on this topic.

But so far, our research may be suggesting a need for more patient-friendly definitions of clinical endpoints, which may help health care providers describe treatment benefits to patients and empower patients to make informed decisions among treatment choices.

Have you found anything counterintuitive in your research?

A word of caution about counterintuitive findings: they may be less likely to be replicated and we may want to examine the results of a similar study to see if the findings hold up. We’d take a similar approach for unsurprising or expected findings too, in that we’d want to see if these results are replicated before drawing conclusions. That’s one reason that we don’t propose policy based solely on one research study. It’s important to critically analyze each study and its findings in the context of other research. We also need to account for a study’s limitations.

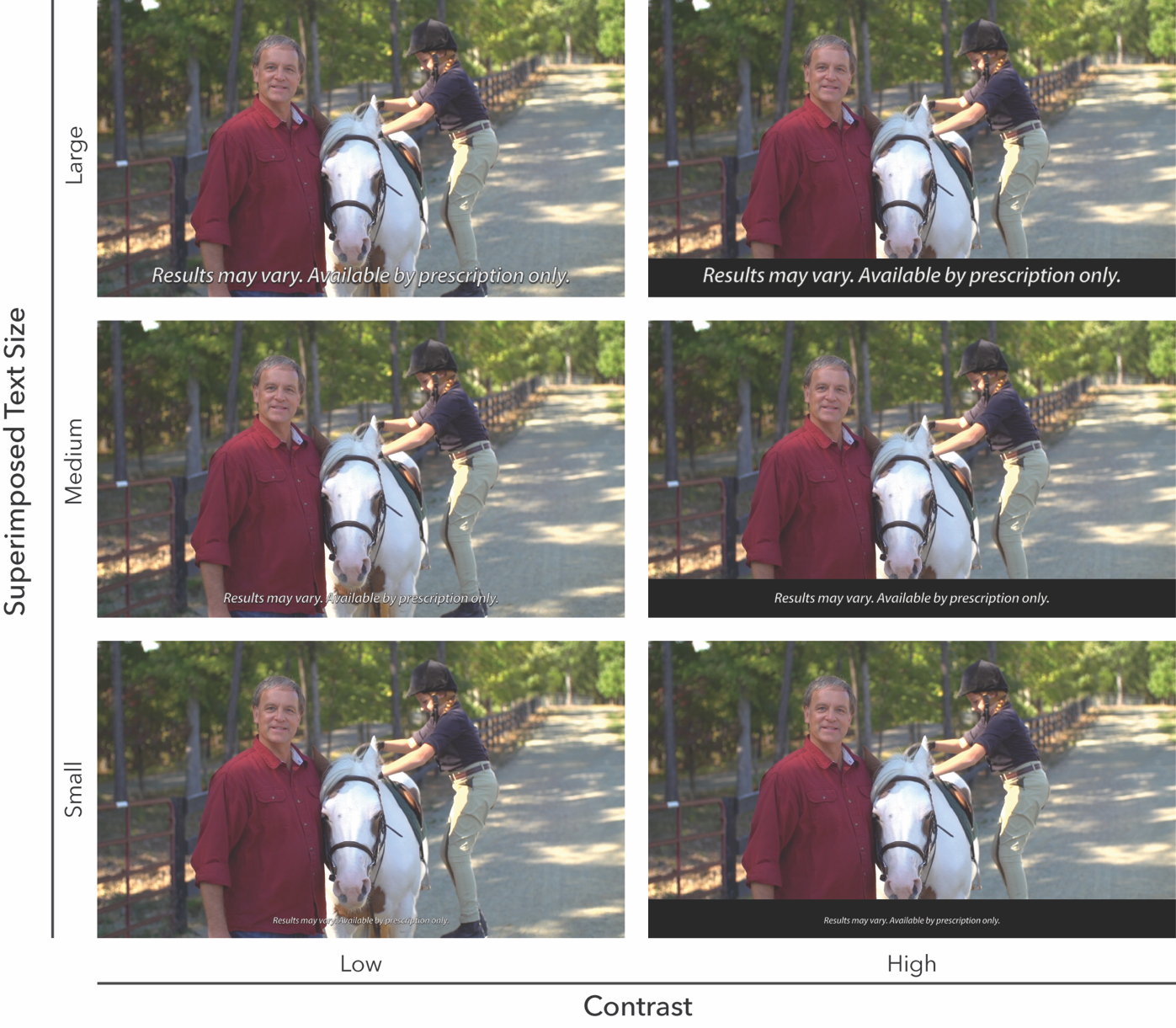

That being said, we had one recent surprising finding involving superimposed text, or text over an image that is generally displayed at the bottom of a screen or presentation that often describes risk information, in direct-to-consumer television advertising. The study authors were surprised that participants who viewed “low contrast” superimposed text (white text over the video image) were more likely to be aware of the text than participants viewing “high contrast” superimposed text (white text over a black field). It would be interesting to see another study that explores the issue of “high contrast” and “low contrast” text.

How are your research priorities changing in the time of technological change and the COVID-19 pandemic?

There is no doubt the times are changing! The amount of drug product promotion on the Internet is exploding. As an example, the Form 2253 submissions (the FDA form that companies fill out and submit to the agency with their promotional materials at the time of first use) for promotional communications on the Internet are increasing every year.

Our November 2021 workshop with Duke Margolis also identified some growing trends in advertising, such as:

- targeted advertising (advertising directed to a certain audience)

- social media influencers (people with credibility in a specific industry, access to a large audience, and the power of persuasion)

- native advertising (advertising embedded in a media source, so that consumers don’t necessarily know it’s advertising)

- advergames (a game developed to advertise a product)

The pandemic is also helping steer the ship toward digital platforms. As you might expect, COVID-19 has driven many in-person conversations between drug companies and health care providers into the virtual space.

These issues are important to explore in social science research projects.

What is on the 2022 research agenda?

We have a busy year ahead and an ambitious research agenda. We are going to be looking at the effects of product endorsements and implied claims (or benefit claims that aren’t overtly expressed but can be reasonably inferred). We are also going to investigate how descriptions of a drug’s “mechanism of action” (or how it works) affect people’s understanding and impressions of that drug.

In addition, we are going to explore how consumers and health care providers make trade-offs in terms of safety and efficacy. For example, are people willing to accept less benefits from a drug if it is easier to use? Will they trade one risk for another?

Any final thoughts on social science research?

As we know, FDA is a science-based agency, with science underpinning and informing all of our decisions. Social science is part of that. It is important for FDA to understand how health care providers and patients perceive and make behavioral decisions based on prescription drug information. These insights may help inform the agency’s development of guidances, policies, and rulemakings. They may also influence how OPDP reviews promotional materials. And on a larger level, OPDP’s findings contribute to the broader field of research into the effect of prescription drug promotion on consumer behavior.

Our team provides scientific insight into how materials about these drugs shape the way people make treatment decisions, and how we can work with industry and other stakeholders to help improve these communications to advance public health.

And finally, I’ve used the word team throughout this interview. That is intentional. Our research team collaborates closely to advance the social science research agenda. I want to acknowledge my colleagues Kevin Betts, Amie O’Donoghue, and Helen Sullivan for their dedication to this important work.