10 Search Results for "NETs"

Tapping Into The Brain’s Primary Motor Cortex

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you’re like me, you might catch yourself during the day in front of a computer screen mindlessly tapping your fingers. (I always check first to be sure my mute button is on!) But all that tapping isn’t as mindless as you might think.

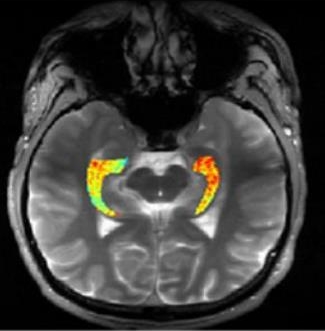

While a research participant performs a simple motor task, tapping her fingers together, this video shows blood flow within the folds of her brain’s primary motor cortex (gray and white), which controls voluntary movement. Areas of high brain activity (yellow and red) emerge in the omega-shaped “hand-knob” region, the part of the brain controlling hand movement (right of center) and then further back within the primary somatic cortex (which borders the motor cortex toward the back of the head).

About 38 seconds in, the right half of the video screen illustrates that the finger tapping activates both superficial and deep layers of the primary motor cortex. In contrast, the sensation of a hand being brushed (a sensory task) mostly activates superficial layers, where the primary sensory cortex is located. This fits with what we know about the superficial and deep layers of the hand-knob region, since they are responsible for receiving sensory input and generating motor output to control finger movements, respectively [1].

The video showcases a new technology called zoomed 7T perfusion functional MRI (fMRI). It was an entry in the recent Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest, supported by NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative.

The technology is under development by an NIH-funded team led by Danny J.J. Wang, University of Southern California Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, Los Angeles. Zoomed 7T perfusion fMRI was developed by Xingfeng Shao and brought to life by the group’s medical animator Jim Stanis.

Measuring brain activity using fMRI to track perfusion is not new. The brain needs a lot of oxygen, carried to it by arteries running throughout the head, to carry out its many complex functions. Given the importance of oxygen to the brain, you can think of perfusion levels, measured by fMRI, as a stand-in measure for neural activity.

There are two things that are new about zoomed 7T perfusion fMRI. For one, it uses the first ultrahigh magnetic field imaging scanner approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The technology also has high sensitivity for detecting blood flow changes in tiny arteries and capillaries throughout the many layers of the cortex [2].

Compared to previous MRI methods with weaker magnets, the new technique can measure blood flow on a fine-grained scale, enabling scientists to remove unwanted signals (“noise”) such as those from surface-level arteries and veins. Getting an accurate read-out of activity from region to region across cortical layers can help scientists understand human brain function in greater detail in health and disease.

Having shown that the technology works as expected during relatively mundane hand movements, Wang and his team are now developing the approach for fine-grained 3D mapping of brain activity throughout the many layers of the brain. This type of analysis, known as mesoscale mapping, is key to understanding dynamic activities of neural circuits that connect brain cells across cortical layers and among brain regions.

Decoding circuits, and ultimately rewiring them, is a major goal of NIH’s BRAIN Initiative. Zoomed 7T perfusion fMRI gives us a window into 4D biology, which is the ability to watch 3D objects over time scales in which life happens, whether it’s playing an elaborate drum roll or just tapping your fingers.

References:

[1] Neuroanatomical localization of the ‘precentral knob’ with computed tomography imaging. Park MC, Goldman MA, Park MJ, Friehs GM. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2007;85(4):158-61.

[2]. Laminar perfusion imaging with zoomed arterial spin labeling at 7 Tesla. Shao X, Guo F, Shou Q, Wang K, Jann K, Yan L, Toga AW, Zhang P, Wang D.J.J bioRxiv 2021.04.13.439689.

Links:

Brain Basics: Know Your Brain (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke)

Laboratory of Functional MRI Technology (University of Southern California Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute)

The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; Office of the Director

Can Autoimmune Antibodies Explain Blood Clots in COVID-19?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For people with severe COVID-19, one of the most troubling complications is abnormal blood clotting that puts them at risk of having a debilitating stroke or heart attack. A new study suggests that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, doesn’t act alone in causing blood clots. The virus seems to unleash mysterious antibodies that mistakenly attack the body’s own cells to cause clots.

The NIH-supported study, published in Science Translational Medicine, uncovered at least one of these autoimmune antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies in about half of blood samples taken from 172 patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Those with higher levels of the destructive autoantibodies also had other signs of trouble. They included greater numbers of sticky, clot-promoting platelets and NETs, webs of DNA and protein that immune cells called neutrophils spew to ensnare viruses during uncontrolled infections, but which can lead to inflammation and clotting. These observations, coupled with the results of lab and mouse studies, suggest that treatments to control those autoantibodies may hold promise for preventing the cascade of events that produce clots in people with COVID-19.

Our blood vessels normally strike a balance between producing clotting and anti-clotting factors. This balance keeps us ready to seal up vessels after injury, but otherwise to keep our blood flowing at just the right consistency so that neutrophils and platelets don’t stick and form clots at the wrong time. But previous studies have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 can tip the balance toward promoting clot formation, raising questions about which factors also get activated to further drive this dangerous imbalance.

To learn more, a team of physician-scientists, led by Yogendra Kanthi, a newly recruited Lasker Scholar at NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and his University of Michigan colleague Jason S. Knight, looked to various types of aPL autoantibodies. These autoantibodies are a major focus in the Knight Lab’s studies of an acquired autoimmune clotting condition called antiphospholipid syndrome. In people with this syndrome, aPL autoantibodies attack phospholipids on the surface of cells including those that line blood vessels, leading to increased clotting. This syndrome is more common in people with other autoimmune or rheumatic conditions, such as lupus.

It’s also known that viral infections, including COVID-19, produce a transient increase in aPL antibodies. The researchers wondered whether those usually short-lived aPL antibodies in COVID-19 could trigger a condition similar to antiphospholipid syndrome.

The researchers showed that’s exactly the case. In lab studies, neutrophils from healthy people released twice as many NETs when cultured with autoantibodies from patients with COVID-19. That’s remarkably similar to what had been seen previously in such studies of the autoantibodies from patients with established antiphospholipid syndrome. Importantly, their studies in the lab further suggest that the drug dipyridamole, used for decades to prevent blood clots, may help to block that antibody-triggered release of NETs in COVID-19.

The researchers also used mouse models to confirm that autoantibodies from patients with COVID-19 actually led to blood clots. Again, those findings closely mirror what happens in mouse studies testing the effects of antibodies from patients with the most severe forms of antiphospholipid syndrome.

While more study is needed, the findings suggest that treatments directed at autoantibodies to limit the formation of NETs might improve outcomes for people severely ill with COVID-19. The researchers note that further study is needed to determine what triggers autoantibodies in the first place and how long they last in those who’ve recovered from COVID-19.

The researchers have already begun enrolling patients into a modest scale clinical trial to test the anti-clotting drug dipyridamole in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19, to find out if it can protect against dangerous blood clots. These observations may also influence the design of the ACTIV-4 trial, which is testing various antithrombotic agents in outpatients, inpatients, and convalescent patients. Kanthi and Knight suggest it may also prove useful to test infected patients for aPL antibodies to help identify and improve treatment for those who may be at especially high risk for developing clots. The hope is this line of inquiry ultimately will lead to new approaches for avoiding this very troubling complication in patients with severe COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] Prothrombotic autoantibodies in serum from patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Zuo Y, Estes SK, Ali RA, Gandhi AA, Yalavarthi S, Shi H, Sule G, Gockman K, Madison JA, Zuo M, Yadav V, Wang J, Woodard W, Lezak SP, Lugogo NL, Smith SA, Morrissey JH, Kanthi Y, Knight JS. Sci Transl Med. 2020 Nov 2:eabd3876.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute/NIH)

Kanthi Lab (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD)

Knight Lab (University of Michigan)

ACTIV (NIH)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Building a Better Bacterial Trap for Sepsis

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Spiders spin webs to catch insects for dinner. It turns out certain human immune cells, called neutrophils, do something similar to trap bacteria in people who develop sepsis, an uncontrolled, systemic infection that poses a major challenge in hospitals.

When activated to catch sepsis-causing bacteria or other pathogens, neutrophils rupture and spew sticky, spider-like webs made of DNA and antibacterial proteins. Here in red you see one of these so-called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that’s ensnared Staphylococcus aureus (green), a type of bacteria known for causing a range of illnesses from skin infections to pneumonia.

Yet this image, which comes from Kandace Gollomp and Mortimer Poncz at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, is much more than a fascinating picture. It demonstrates a potentially promising new way to treat sepsis.

The researchers’ strategy involves adding a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4), which is released by clot-forming blood platelets, to the NETs. PF4 readily binds to NETs and enhances their capture of bacteria. A modified antibody (white), which is a little hard to see, coats the PF4-bound NET above. This antibody makes the NETs even better at catching and holding onto bacteria. Other immune cells then come in to engulf and clean up the mess.

Until recently, most discussions about NETs assumed they were causing trouble, and therefore revolved around how to prevent or get rid of them while treating sepsis. But such strategies faced a major obstacle. By the time most people are diagnosed with sepsis, large swaths of these NETs have already been spun. In fact, destroying them might do more harm than good by releasing entrapped bacteria and other toxins into the bloodstream.

In a recent study published in the journal Blood, Gollomp’s team proposed flipping the script [1]. Rather than prevent or destroy NETs, why not modify them to work even better to fight sepsis? Their idea: Make NETs even stickier to catch more bacteria. This would lower the number of bacteria and help people recover from sepsis.

Gollomp recalled something lab member Anna Kowalska had noted earlier in unrelated mouse studies. She’d observed that high levels of PF4 were protective in mice with sepsis. Gollomp and her colleagues wondered if the PF4 might also be used to reinforce NETs. Sure enough, Gollomp’s studies showed that PF4 will bind to NETs, causing them to condense and resist break down.

Subsequent studies in mice and with human NETs cast in a synthetic blood vessel suggest that this approach might work. Treatment with PF4 greatly increased the number of bacteria captured by NETs. It also kept NETs intact and holding tightly onto their toxic contents. As a result, mice with sepsis fared better.

Of course, mice are not humans. More study is needed to see if the same strategy can help people with sepsis. For example, it will be important to determine if modified NETs are difficult for the human body to clear. Also, Gollomp thinks this approach might be explored for treating other types of bacterial infections.

Still, the group’s initial findings come as encouraging news for hospital staff and administrators. If all goes well, a future treatment based on this intriguing strategy may one day help to reduce the 270,000 sepsis-related deaths in the U.S. and its estimated more than $24 billion annual price tag for our nation’s hospitals [2, 3].

References:

[1] Fc-modified HIT-like monoclonal antibody as a novel treatment for sepsis. Gollomp K, Sarkar A, Harikumar S, Seeholzer SH, Arepally GM, Hudock K, Rauova L, Kowalska MA, Poncz M. Blood. 2020 Mar 5;135(10):743-754.

[2] Sepsis, Data & Reports, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Feb. 14, 2020.

[3] National inpatient hospital costs: The most expensive conditions by payer, 2013: Statistical Brief #204. Torio CM, Moore BJ. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 May.

Links:

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Kandace Gollomp (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PA)

Mortimer Poncz (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PA)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Teaming Magnetic Bacteria with Nanoparticles for Better Drug Delivery

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Nanoparticles hold great promise for delivering next-generation therapeutics, including those based on CRISPR gene editing tools. The challenge is how to guide these tiny particles through the bloodstream and into the right target tissues. Now, scientists are enlisting some surprising partners in this quest: magnetic bacteria!

First a bit of background. Discovered in the 1960s during studies of bog sediments, “magnetotactic” bacteria contain magnetic, iron-rich particles that enable them to orient themselves to the Earth’s magnetic fields. To explore the potential of these microbes for targeted delivery of nanoparticles, the NIH-funded researchers devised the ingenious system you see in this fluorescence microscopy video. This system features a model blood vessel filled with a liquid that contains both fluorescently-tagged nanoparticles (red) and large swarms of a type of magnetic bacteria called Magnetospirillum magneticum (not visible).

At the touch of a button that rotates external magnetic fields, researchers can wirelessly control the direction in which the bacteria move through the liquid—up, down, left, right, and even “freestyle.” And—get this—the flow created by the synchronized swimming of all these bacteria pushes along any nearby nanoparticles in the same direction, even without any physical contact between the two. In fact, the researchers have found that this bacteria-guided system delivers nanoparticles into target model tissues three times faster than a similar system lacking such bacteria.

How did anyone ever dream this up? Most previous attempts to get nanoparticle-based therapies into diseased tissues have relied on simple diffusion or molecular targeting methods. Because those approaches are not always ideal, NIH-funded researchers Sangeeta Bhatia, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, and Simone Schürle, formerly of MIT and now ETH Zurich, asked themselves: Could magnetic forces be used to propel nanoparticles through the bloodstream?

As a graduate student at ETH Zurich, Schürle had worked to develop and study tiny magnetic robots, each about the size of a cell. Those microbots, called artificial bacterial flagella (ABF), were designed to replicate the movements of bacteria, relying on miniature flagellum-like propellers to move them along in corkscrew-like fashion.

In a study published recently in Science Advances, the researchers found that the miniature robots worked as hoped in tests within a model blood vessel [1]. Using magnets to propel a single microbot, the researchers found that 200-nanometer-sized polystyrene balls penetrated twice as far into a model tissue as they did without the aid of the magnet-driven forces.

At the same time, others in the Bhatia lab were developing bacteria that could be used to deliver cancer-fighting drugs. Schürle and Bhatia wished they could direct those microbial swarms using magnets as they could with the microbots. That’s when they learned about the potential of M. magneticum and developed the experimental system demonstrated in the video above.

The researchers’ next step will be to test their magnetic approach to drug delivery in a mouse model. Ultimately, they think their innovative strategy holds promise for delivering nanoparticles carrying a wide range of therapeutic payloads right to a tumor, infection, or other diseased tissue. It’s yet another example of how basic research combined with outside-the-box thinking can lead to surprisingly creative solutions with real potential to improve human health.

References:

[1] Synthetic and living micropropellers for convection-enhanced nanoparticle transport. Schürle S, Soleimany AP, Yeh T, Anand GM, Häberli M, Fleming HE, Mirkhani N, Qiu F, Hauert S, Wang X, Nelson BJ, Bhatia SN. Sci Adv. 2019 Apr 26;5(4):eaav4803.

Links:

Nanotechnology (NIH)

What are genome editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Sangeeta Bhatia (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA)

Simone Schürle-Finke (ETH Zurich, Switzerland)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Distinctive Brain ‘Subnetwork’ Tied to Feeling Blue

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: :iStock/kieferpix

Experiencing a range of emotions is a normal part of human life, but much remains to be discovered about the neuroscience of mood. In a step toward unraveling some of those biological mysteries, researchers recently identified a distinctive pattern of brain activity associated with worsening mood, particularly among people who tend to be anxious.

In the new study, researchers studied 21 people who were hospitalized as part of preparation for epilepsy surgery, and took continuous recordings of the brain’s electrical activity for seven to 10 days. During that same period, the volunteers also kept track of their moods. In 13 of the participants, low mood turned out to be associated with stronger activity in a “subnetwork” that involved crosstalk between the brain’s amygdala, which mediates fear and other emotions, and the hippocampus, which aids in memory.

Rare Disease Mystery: Nodding Syndrome May Be Linked to Parasitic Worm

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Village in the East Africa nation of Uganda

Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

In the early 1960s, reports began to surface that some children living in remote villages in East Africa were suffering mysterious episodes of “head nodding.” The condition, now named nodding syndrome, is recognized as a rare and devastating form of epilepsy. There were hints that the syndrome might be caused by a parasitic worm called Onchocerca volvulus, which is transmitted through the bites of blackflies. But no one had been able to tie the parasitic infection directly to the nodding heads.

Now, NIH researchers and their international colleagues think they’ve found the missing link. The human immune system turns out to be a central player. After analyzing blood and cerebrospinal fluid of kids with nodding syndrome, they detected a particular antibody at unusually high levels [1]. Further studies suggest the immune system ramps up production of that antibody to fight off the parasite. The trouble is those antibodies also react against a protein in healthy brain tissue, apparently leading to progressive cognitive dysfunction, neurological deterioration, head nodding, and potentially life-threatening seizures.

The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine, have important implications for the treatment and prevention of not only nodding syndrome, but perhaps other autoimmune-related forms of epilepsy. As people in the United States and around the globe today observe the 10th anniversary of international Rare Disease Day, this work provides yet another example of how rare disease research can shed light on more common diseases and fundamental aspects of human biology.

Treating Zika Infection: Repurposed Drugs Show Promise

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH

In response to the health threat posed by the recent outbreak of Zika virus in Latin America and its recent spread to Puerto Rico and Florida, researchers have been working at a furious pace to learn more about the mosquito-borne virus. Considerable progress has been made in understanding how Zika might cause babies to be born with unusually small heads and other abnormalities and in developing vaccines that may guard against Zika infection.

Still, there remains an urgent need to find drugs that can be used to treat people already infected with the Zika virus. A team that includes scientists at NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) now has some encouraging news on this front. By testing 6,000 FDA-approved drugs and experimental chemical compounds on Zika-infected human cells in the lab, they’ve shown that some existing drugs might be repurposed to fight Zika infection and prevent the virus from harming the developing brain [1]. While additional research is needed, the new findings suggest it may be possible to speed development and approval of new treatments for Zika infection.

Brain Imaging: Advance Aims for Epilepsy’s Hidden Hot Spots

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Reddy Lab, University of Pennsylvania

For many of the 65 million people around the world with epilepsy, modern medications are able to keep the seizures under control. When medications fail, as they do in about one-third of people with epilepsy, surgery to remove affected brain tissue without compromising function is a drastic step, but offers a potential cure. Unfortunately, not all drug-resistant patients are good candidates for such surgery for a simple reason: their brains appear normal on traditional MRI scans, making it impossible to locate precisely the source(s) of the seizures.

Now, in a small study published in Science Translational Medicine [1], NIH-funded researchers report progress towards helping such people. Using a new MRI method, called GluCEST, that detects concentrations of the nerve-signaling chemical glutamate in brain tissue [2], researchers successfully pinpointed seizure-causing areas of the brain in four of four volunteers with drug-resistant epilepsy and normal traditional MRI scans. While the findings are preliminary and must be confirmed by larger studies, researchers are hopeful that GluCEST, which takes about 30 minutes, may open the door to new ways of treating this type of epilepsy.