California

How COVID-19 Took Hold in North America and Europe

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It was nearly 10 months ago on January 15 that a traveler returned home to the Seattle area after visiting family in Wuhan, China. A few days later, he started feeling poorly and became the first laboratory-confirmed case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States. The rest is history.

However, new evidence published in the journal Science suggests that this first COVID-19 case on the West Coast didn’t snowball into the current epidemic. Instead, while public health officials in Washington state worked tirelessly and ultimately succeeded in containing its sustained transmission, the novel coronavirus slipped in via another individual about two weeks later, around the beginning of February.

COVID-19 is caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Last winter, researchers sequenced the genetic material from the SARS-CoV-2 that was isolated from the returned Seattle traveler. While contact tracing didn’t identify any spread of this particular virus, dubbed WA1, questions arose when a genetically similar virus known as WA2 turned up in Washington state. Not long after, WA2-like viruses then appeared in California; British Columbia, Canada; and eventually 3,000 miles away in Connecticut. By mid-March, this WA2 cluster accounted for the vast majority—85 percent—of the cases in Washington state.

But was it possible that the WA2 cluster is a direct descendent of WA1? Did WA1 cause an unnoticed chain of transmission over several weeks, making the Seattle the epicenter of the outbreak in North America?

To answer those questions and others from around the globe, Michael Worobey, University of Arizona, Tucson, and his colleagues drew on multiple sources of information. These included data peretaining to viral genomes, airline passenger flow, and disease incidence in China’s Hubei Province and other places that likely would have influenced the probability that infected travelers were moving the virus around the globe. Based on all the evidence, the researchers simulated the outbreak more than 1,000 times on a computer over a two-month period, beginning on January 15 and assuming the epidemic started with WA1. And, not once did any of their simulated outbreaks match up to the actual genome data.

Those findings suggest to the researchers that the idea WA1 is responsible for all that came later is exceedingly unlikely. The evidence and simulations also appear to rule out the notion that the earliest cases in Washington state entered the United States by way of Canada. A deep dive into the data suggests a more likely scenario is that the outbreak was set off by one or more introductions of genetically similar viruses from China to the West Coast. Though we still don’t know exactly where, the Seattle area is the most likely site given the large number of WA2-like viruses sampled there.

Worobey’s team conducted a second analysis of the outbreak in Europe, and those simulations paint a similar picture to the one in the United States. The researchers conclude that the first known case of COVID-19 in Europe, arriving in Germany on January 20, led to a relatively small number of cases before being stamped out by aggressive testing and contact tracing efforts. That small, early outbreak probably didn’t spark the later one in Northern Italy, which eventually spread to the United States.

Their findings also show that the chain of transmission from China to Italy to New York City sparked outbreaks on the East Coast slightly later in February than those that spread from China directly to Washington state. It confirms that the Seattle outbreak was indeed the first, predating others on the East Coast and in California.

The findings in this report are yet another reminder of the value of integrating genome surveillance together with other sources of data when it comes to understanding, tracking, and containing the spread of COVID-19. They also show that swift and decisive public health measures to contain the virus worked when SARS-CoV-2 first entered the United States and Europe, and can now serve as models of containment.

Since the suffering and death from this pandemic continues in the United States, this historical reconstruction from early in 2020 is one more reminder that all of us have the opportunity and the responsibility to try to limit further spread. Wear your mask when you are outside the home; maintain physical distancing; wash your hands frequently; and don’t congregate indoors, where the risks are greatest. These lessons will enable us to better anticipate, prevent, and respond to additional outbreaks of COVID-19 or any other novel viruses that may arise in the future.

Reference:

[1] The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe and North America. Worobey M, Pekar J, Larsen BB, Nelson MI, Hill V, Joy JB, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Wertheim JO, Lemey P. Science. 2020 Sep 10:eabc8169 [Epub ahead of print]

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Michael Worobey (University of Arizona, Tucson)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Fogarty International Center; National Library of Medicine

Pop-Up Testing Lab Shows Volunteer Spirit Against Deadly Pandemic

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

On March 19, 2020, California became the first U. S. state to issue a stay-at-home order to halt the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. The order shuttered research labs around the state, and thousands of scientists began sheltering at home and shifting their daily focus to writing papers and grants, analyzing data from past experiments, and catching up on their scientific reading.

That wasn’t the case for everyone. Some considered the order as presenting a perfect opportunity to volunteer, sometimes outside of their fields of expertise, to help their state and communities respond to the pandemic.

One of those willing to pitch in is Jennifer Doudna, University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) and executive director of the school’s Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI), a partnership with the University of California, San Francisco (UC San Francisco). She is also recognized as a pioneer in the development of the popular gene-editing technology called CRISPR.

Doudna, an NIH-supported structural biochemist with no experience in virology or clinical diagnostics, decided that she and her IGI colleagues could establish a pop-up testing lab at their facility. Their job: boost the SARS-CoV-2 testing capacity in her community.

It was a great idea, but a difficult one to execute. The first daunting step was acquiring Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certification. This U. S. certification ensures that quality standards are met for laboratory testing of human blood, body fluid, and other specimens for medical purposes. CLIA certification is required not only to perform such testing in the IGI lab space, but for Doudna’s graduate students, postdocs, and volunteers to process patient samples.

Still, fate was on their side. Doudna and her team partnered with UC Berkeley’s University Health Services to extend the student health center’s existing CLIA certification to the IGI space. And because of the urgency of the pandemic, federal review of the extension request was expedited and granted in a few weeks.

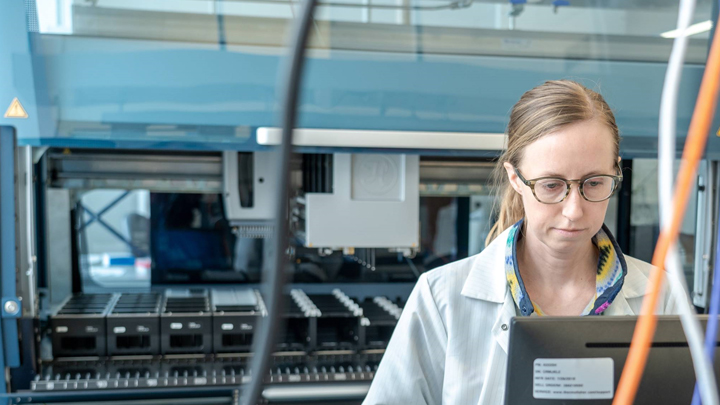

The next challenge was technological. Doudna’s team had to make sure that its diagnostic system was as good or better than those of other SARS-CoV-2 testing platforms. With great care and attention to lab safety, the team began assembling two parallel workstreams: one a semi-manual method to get going right away and the other a faster, automated, robotic method to transition to when ready.

Soon, patient samples began arriving in the lab to be tested for the presence of genetic material (RNA) from SARS-CoV-2, an indication that a person is infected with the virus. The diagnostic system was also soon humming along, with Doudna’s automated workstream having the capacity to process 384 samples in parallel.

The pop-up lab—known formally as the IGI SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic Testing Laboratory—is funded through philanthropy and staffed by more than 50 volunteers from IGI, UC Berkeley, UC San Francisco, and local data-management companies. Starting on April 6, the lab was fully operational, capable of running hundreds of tests daily with a 24-hour turnaround time for results. A positive test requires that at least two out of three SARS-CoV-2 genomic targets return a positive signal, and the method uses de-identified barcoded sample data to protect patient privacy.

Doudna intends to keep the pop-up lab open as long as her community needs it. So far, they’ve provided testing to UC Berkeley students and staff, first responders (including the entire Berkeley Fire Department), and several members of the city’s homeless population. She says that availability of samples will soon be the rate-limiting step in their sample-analysis pipeline and hopes continued partnerships with local health officials will enable them to work at full capacity to deliver thousands of test results rapidly.

Doudna says she’s been amazed by the team spirit of her lab members and other local colleagues who have come together around a crisis. They’ve gotten the job done by contributing their different skills and resources, including behind-the-scenes efforts by the university’s leadership and staff, philanthropists, city officials, and state government workers.

Although Doudna and her team intend to publish their work to help others follow suit [1], she says the experience has also provided her with many intangible rewards. It has highlighted the value of resilience and adaptation, as well as given her a newfound appreciation for the complexity and precision of operations in the commercial clinical labs that are a routine part of our medical care.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have thrust all of us into a time warp, in which weeks sometimes feel like months, there is much to do. The amount of work needed to tame this virus is significant and requires an all-hands-on-deck mentality, which NIH and the biomedical research community have embraced fully.

Doudna is not alone. Other labs around the country are engaged in similar efforts. At the NIH’s main campus in Bethesda, MD, staff at the clinical laboratory in the Clinical Center rapidly set up testing for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, and have now tested more than 1,000 NIH staff. Researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard partnered with the city of Cambridge, MA, to pilot COVID-19 surveillance in homeless shelters and skilled nursing and assisted living facilities located there.

Hats off to everyone who goes the extra mile to get us through this tough time. I am so gratified when, guided by compassion and dogged determination of the human spirit, science leads the way and provides much needed hope for our future.

Reference:

[1] Blueprint for a Pop-up SARS-CoV-2 Testing Lab. Innovative Genomics Institute SARS-CoV-2 Testing Consortium, Hockemeyer D, Fyodor U, Doudna JA. 2020. medRxiv. Preprint posted on April 12, 2020.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

CLIA Law & Regulations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Innovative Genomic Institute (Berkeley, CA)

Doudna Lab (University of California, Berkeley)