cancer drugs

Wearable Sensor Promises More Efficient Early Cancer Drug Development

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Wearable electronic sensors hold tremendous promise for improving human health and wellness. That promise already runs the gamut from real-time monitoring of blood pressure and abnormal heart rhythms to measuring alcohol consumption and even administering vaccines.

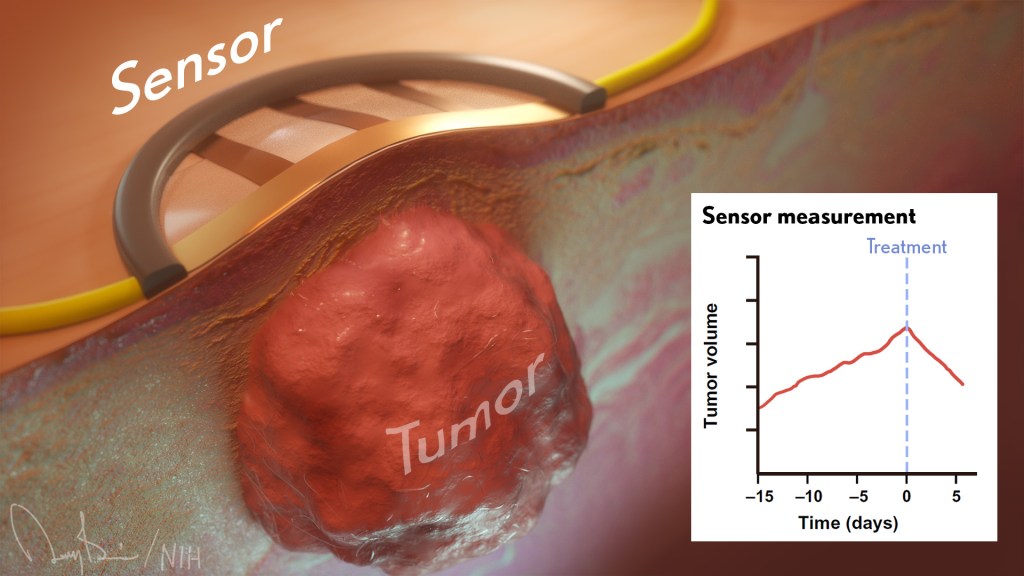

Now a new study published in the journal Science Advances [1] demonstrates the promise of wearables also extends to the laboratory. A team of engineers has developed a flexible, adhesive strip that, at first glance, looks like a Band-Aid. But this “bandage” actually contains an ultra-sensitive, battery-operated sensor that’s activated when placed on the skin of mouse models used to study possible new cancer drugs.

This sensor is so sensitive that it can detect, in real time, changes in the size of a tumor down to one-hundredth of a millimeter. That’s about the thickness of the plastic cling wrap you likely have in your kitchen! The device beams those measures to a smartphone app, capturing changes in tumor growth minute by minute over time.

The goal is to determine much sooner—and with greater automation and precision—which potential drug candidates undergoing early testing in the lab best inhibit tumor growth and, consequently, should be studied further. In their studies in mouse models of cancer, researchers found the new sensor could detect differences between tumors treated with an active drug and those treated with a placebo within five hours. Those quick results also were validated using more traditional methods to confirm their accuracy.

The device is the work of a team led by Alex Abramson, a former post-doc with Zhenan Bao, Stanford University’s School of Engineering, Palo Alto, CA. Abramson has since launched his own lab at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta.

The Stanford team began looking for a technological solution after realizing the early testing of potential cancer drugs typically requires researchers to make tricky measurements using pincer-like calipers by hand. Not only is the process tedious and slow, it’s less than an ideal way to capture changes in soft tissues with the desired precision. The imprecision can also lead to false leads that won’t pan out further along in the drug development pipeline, at great time and expense to their developers.

To refine the process, the NIH-supported team turned to wearable technology and recent advances in flexible electronic materials. They developed a device dubbed FAST (short for Flexible Autonomous Sensor measuring Tumors). Its sensor, embedded in a skin patch, is composed of a flexible and stretchable, skin-like polymer with embedded gold circuitry.

Here’s how FAST works: Coated on top of the polymer skin patch is a layer of gold. When stretched, it forms small cracks that change the material’s electrical conductivity. As the material stretches, even slightly, the number of cracks increases, causing the electronic resistance in the sensor to increase as well. As the material contracts, any cracks come back together, and conductivity improves.

By picking up on those changes in conductivity, the device measures precisely the strain on the polymer membrane—an indication of whether the tumor underneath is stable, growing, or shrinking—and transmits that data to a smartphone. Based on that information, potential therapies that are linked to rapid tumor shrinkage can be fast-tracked for further study while those that allow a tumor to continue growing can be cast aside.

The researchers are continuing to test their sensor in more cancer models and with more therapies to extend these initial findings. Already, they have identified at least three significant advantages of their device in early cancer drug testing:

• FAST is non-invasive and captures precise measurements on its own.

• It can provide continuous monitoring, for weeks, months, or over the course of study.

• The flexible sensor fully surrounds the tumor and can therefore detect 3D changes in shape that would be hard to pick up otherwise in real-time with existing technologies.

By now, you are probably asking yourself: Could FAST also be applied as a wearable for cancer patients to monitor in real-time whether an approved chemotherapy regimen is working? It is too early to say. So far, FAST has not been tested in people. But, as highlighted in this paper, FAST is off to, well, a fast start and points to the vast potential of wearables in human health, wellness, and also in the lab.

Reference:

[1] A flexible electronic strain sensor for the real-time monitoring of tumor regression. Abramson A, Chan CT, Khan Y, Mermin-Bunnell A, Matsuhisa N, Fong R, Shad R, Hiesinger W, Mallick P, Gambhir SS, Bao Z. Sci Adv. 2022 Sep 16;8(37):eabn6550.

Links:

Stanford Wearable Electronics Initiative (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA)

Bao Group (Stanford University)

Abramson Lab (Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

NCI Support for Basic Science Paves Way for Kidney Cancer Drug Belzutifan

Posted on by Norman "Ned" Sharpless, M.D., National Cancer Institute

There’s exciting news for people with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, a rare genetic disorder that can lead to cancerous and non-cancerous tumors in multiple organs, including the brain, spinal cord, kidney, and pancreas. In August 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved belzutifan (Welireg), a new drug that has been shown in a clinical trial led by National Cancer Institute (NCI) researchers to shrink some tumors associated with VHL disease [1], which is caused by inherited mutations in the VHL tumor suppressor gene.

As exciting as this news is, relatively few people have this rare disease. The greater public health implication of this advancement is for people with sporadic, or non-inherited, clear cell kidney cancer, which is by far the most common subtype of kidney cancer, with more than 70,000 cases and about 14,000 deaths per year. Most cases of sporadic clear cell kidney cancer are caused by spontaneous mutations in the VHL gene.

This advancement is also a great story of how decades of support for basic science through NCI’s scientists in the NIH Intramural Research Program and its grantees through extramural research funding has led to direct patient benefit. And it’s a reminder that we never know where basic science discoveries might lead.

Belzutifan works by disrupting the process by which the loss of VHL in a tumor turns on a series of molecular processes. These processes involve the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) transcription factor and one of its subunits, HIF-2α, that lead to tumor formation.

The unraveling of the complex relationship among VHL, the HIF pathway, and cancer progression began in 1984, when Bert Zbar, Laboratory of Immunobiology, NCI-Frederick; and Marston Linehan, NCI’s Urologic Oncology Branch, set out to find the gene responsible for clear cell kidney cancer. At the time, there were no effective treatments for advanced kidney cancer, and 80 percent of patients died within two years.

Zbar and Linehan started by studying patients with sporadic clear cell kidney cancer, but then turned their focus to investigations of people affected with VHL disease, which predisposes a person to developing clear cell kidney cancer. By studying the patients and the genetic patterns of tumors collected from these patients, the researchers hypothesized that they could find genes responsible for kidney cancer.

Linehan established a clinical program at NIH to study and manage VHL patients, which facilitated the genetic studies. It took nearly a decade, but, in 1993, Linehan, Zbar, and Michael Lerman, NCI-Frederick, identified the VHL gene, which is mutated in people with VHL disease. They soon discovered that tumors from patients with sporadic clear cell kidney cancer also have mutations in this gene.

Subsequently, with NCI support, William G. Kaelin Jr., Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, discovered that VHL is a tumor suppressor gene that, when inactivated, leads to the accumulation of HIF.

Another NCI grantee, Gregg L. Semenza, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, identified HIF as a transcription factor. And Peter Ratcliffe, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, discovered that HIF plays a role in blood vessel development and tumor growth.

Kaelin and Ratcliffe simultaneously showed that the VHL protein tags a subunit of HIF for destruction when oxygen levels are high. These results collectively answered a very old question in cell biology: How do cells sense the intracellular level of oxygen?

Subsequent studies by Kaelin, with NCI’s Richard Klausner and Linehan, revealed the critical role of HIF in promoting the growth of clear cell kidney cancer. This work ultimately focused on one member of the HIF family, the HIF-2α subunit, as the key mediator of clear cell kidney cancer growth.

The fundamental work of Kaelin, Semenza, and Ratcliffe earned them the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. It also paved the way for drug discovery efforts that target numerous points in the pathway leading to clear cell kidney cancer, including directly targeting the transcriptional activity of HIF-2α with belzutifan.

Clinical trials of belzutifan, including several supported by NCI, demonstrated potent anti-cancer activity in VHL-associated kidney cancer, as well as other VHL-associated tumors, leading to the aforementioned recent FDA approval. This is an important development for patients with VHL disease, providing a first-in-class therapy that is effective and well-tolerated.

We believe this is only the beginning for belzutifan’s use in patients with cancer. A number of trials are now studying the effectiveness of belzutifan for sporadic clear cell kidney cancer. A phase 3 trial is ongoing, for example, to look at the effectiveness of belzutifan in treating people with advanced kidney cancer. And promising results from a phase 2 study show that belzutifan, in combination with cabozantinib, a widely used agent to treat kidney cancer, shrinks tumors in patients previously treated for metastatic clear cell kidney cancer [2].

This is a great scientific story. It shows how studies of familial cancer and basic cell biology lead to effective new therapies that can directly benefit patients. I’m proud that NCI’s support for basic science, both intramurally and extramurally, is making possible many of the discoveries leading to more effective treatments for people with cancer.

References:

[1] Belzutifan for Renal Cell Carcinoma in von Hippel-Lindau Disease. Jonasch E, Donskov F, Iliopoulos O, Rathmell WK, Narayan VK, Maughan BL, Oudard S, Else T, Maranchie JK, Welsh SJ, Thamake S, Park EK, Perini RF, Linehan WM, Srinivasan R; MK-6482-004 Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021 Nov 25;385(22):2036-2046.

[2] Phase 2 study of the oral hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF-2α) inhibitor MK-6482 in combination with cabozantinib in patients with advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Choueiri TK et al. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Feb 20;39(6_suppl): 272-272.

Links:

Von Hippel-Lindau Disease (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Belzutifan Approved to Treat Tumors Linked to Inherited Disorder VHL, Cancer Currents Blog, National Cancer Institute, September 21, 2021.

The Long Road to Understanding Kidney Cancer (Intramural Research Program/NIH)

[Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s institutes and centers to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog as a way to highlight some of the cool science that they support and conduct. This is the first in the series of NIH institute and center guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.]

Encouraging News for Kids with Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the headlines and uncertainty surrounding the current COVID-19 pandemic, it’s easy to overlook the important progress that biomedical research is making against other diseases. So, today, I’m pleased to share word of what promises to be the first effective treatment to help young people suffering from the consequences of a painful, often debilitating genetic disorder called neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

This news is particularly meaningful to me because, 30 years ago, I led a team that discovered the gene that underlies NF1. About 1 in 3,000 babies are born with NF1. In about half of those affected, a type of tumor called a plexiform neurofibroma arises along nerves in the skin, face, and other parts of the body. While plexiform neurofibromas are not cancerous, they grow steadily and can lead to severe pain and a range of other health problems, including vision and hearing loss, hypertension, and mobility issues.

The good news is the results of a phase II clinical trial involving NF1, just published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The trial was led by Brigitte Widemann and Andrea Gross, researchers in the Center for Cancer Research at NIH’s National Cancer Institute.

The trial’s results confirm that a drug originally developed to treat cancer, called selumetinib, can shrink inoperable tumors in many children with NF1. They also establish that the drug can help affected kids make significant improvements in strength, range of motion, and quality of life. While selumetinib is not a cure, and further studies are still needed to see how well the treatment works in the long term, these results suggest that the first effective treatment for NF1 is at last within our reach.

Selumetinib blocks a protein in human cells called MEK. This protein is involved in a major cellular pathway known as RAS that can become dysregulated and give rise to various cancers. By blocking the MEK protein in animal studies and putting the brakes on the RAS pathway when it malfunctions, selumetinib showed great initial promise as a cancer drug.

Selumetinib was first tested several years ago in people with a variety of other cancers, including ovarian and non-small cell lung cancers. The clinical research looked good at first but eventually stalled, and so did much of the initial enthusiasm for selumetinib.

But the enthusiasm picked up when researchers considered repurposing the drug to treat NF1. The neurofibromas associated with the condition were known to arise from a RAS-activating loss of the NF1 gene. It made sense that blocking the MEK protein might blunt the overactive RAS signal and help to shrink these often-inoperable tumors.

An earlier phase 1 safety trial looked promising, showing for the first time that the drug could, in some cases, shrink large NF1 tumors [2]. This fueled further research, and the latest study now adds significantly to that evidence.

In the study, Widemann and colleagues enrolled 50 children with NF1, ranging in age from 3 to 17. Their tumor-related symptoms greatly affected their wellbeing and ability to thrive, including disfigurement, limited strength and motion, and pain. Children received selumetinib alone orally twice a day and went in for assessments at least every four months.

As of March 2019, 35 of the 50 children in the ongoing study had a confirmed partial response, meaning that their tumors had shrunk by more than 20 percent. Most had maintained that response for a year or more. More importantly, the kids also felt less pain and were more able to enjoy life.

It’s important to note that the treatment didn’t work for everyone. Five children stopped taking the drug due to side effects. Six others progressed while on the drug, though five of them had to reduce their dose because of side effects before progressing. Nevertheless, for kids with NF1 and their families, this is a big step forward.

Drug developer AstraZeneca, working together with the researchers, has submitted a New Drug Application to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). While they’re eagerly awaiting the FDA’s decision, the work continues.

The researchers want to learn much more about how the drug affects the health and wellbeing of kids who take it over the long term. They’re also curious whether it could help to prevent the growth of large tumors in kids who begin taking it earlier in the course of the disease, and whether it might benefit other features of the disorder. They will continue to look ahead to other potentially promising treatments or treatment combinations that may further help, and perhaps one day even cure, kids with NF1. So, even while we cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, there are reasons to feel encouraged and grateful for continued progress made throughout biomedical research.

References:

[1] Selumitinib in children with inoperable plexiform neurofibromas. New England Journal of Medicine. Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Whitcomb P, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Bornhorst M, Shah AC, Martin S, Roderick MC, Pichard DC, Carbonell A, Paul SM, Therrien J, Kapustina O, Heisey K, Clapp DW, Zhang C, Peer CJ, Figg WD, Smith M, Glod J, Blakeley JO, Steinberg SM, Venzon DJ, Doyle LA, Widemann BC. 18 March 2020. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. [Epub ahead of publication.]

[2] Activity of selumetinib in neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Whitcomb P, Martin S, Aschbacher-Smith LE, Rizvi TA, Wu J, Ershler R, Wolters P1, Therrien J, Glod J, Belasco JB, Schorry E, Brofferio A, Starosta AJ, Gillespie A, Doyle AL, Ratner N, Widemann BC. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 29;375(26):2550-2560.

Links:

Neurofibromatosis Fact Sheet (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Brigitte Widemann (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Andrea Gross (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

Precision Oncology: Gene Changes Predict Immunotherapy Response

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Adapted from scanning electron micrograph of cytotoxic T cells (red) attacking a cancer cell (white).

Credits: Rita Elena Serda, Baylor College of Medicine; Jill George, NIH

There’s been tremendous excitement in the cancer community recently about the life-saving potential of immunotherapy. In this treatment strategy, a patient’s own immune system is enlisted to control and, in some cases, even cure the cancer. But despite many dramatic stories of response, immunotherapy doesn’t work for everyone. A major challenge has been figuring out how to identify with greater precision which patients are most likely to benefit from this new approach, and how to use that information to develop strategies to expand immunotherapy’s potential.

A couple of years ago, I wrote about early progress on this front, highlighting a small study in which NIH-funded researchers were able to predict which people with colorectal and other types of cancer would benefit from an immunotherapy drug called pembrolizumab (Keytruda®). The key seemed to be that tumors with defects affecting the “mismatch repair” pathway were more likely to benefit. Mismatch repair is involved in fixing small glitches that occur when DNA is copied during cell division. If a tumor is deficient in mismatch repair, it contains many more DNA mutations than other tumors—and, as it turns out, immunotherapy appears to be most effective against tumors with many mutations.

Now, I’m pleased to report more promising news from that clinical trial of pembrolizumab, which was expanded to include 86 adults with 12 different types of mismatch repair-deficient cancers that had been previously treated with at least one type of standard therapy [1]. After a year of biweekly infusions, more than half of the patients had their tumors shrink by at least 30 percent—and, even better, 18 had their tumors completely disappear!

A little more than a decade ago, researchers began adapting a familiar commercial concept to genomics: the barcode. Instead of the black, printed stripes of the Universal Product Codes (UPCs) that we see on everything from package deliveries to clothing tags, they used short, unique snippets of DNA to label cells. These biological “barcodes” enable scientists to distinguish one cell type from another, in much the same way that a supermarket scanner recognizes different brands of cereal.

A little more than a decade ago, researchers began adapting a familiar commercial concept to genomics: the barcode. Instead of the black, printed stripes of the Universal Product Codes (UPCs) that we see on everything from package deliveries to clothing tags, they used short, unique snippets of DNA to label cells. These biological “barcodes” enable scientists to distinguish one cell type from another, in much the same way that a supermarket scanner recognizes different brands of cereal.