eye

Artificial Intelligence Getting Smarter! Innovations from the Vision Field

Posted on by Michael F. Chiang, M.D., National Eye Institute

One of many health risks premature infants face is retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), a leading cause of childhood blindness worldwide. ROP causes abnormal blood vessel growth in the light-sensing eye tissue called the retina. Left untreated, ROP can lead to lead to scarring, retinal detachment, and blindness. It’s the disease that caused singer and songwriter Stevie Wonder to lose his vision.

Now, effective treatments are available—if the disease is diagnosed early and accurately. Advancements in neonatal care have led to the survival of extremely premature infants, who are at highest risk for severe ROP. Despite major advancements in diagnosis and treatment, tragically, about 600 infants in the U.S. still go blind each year from ROP. This disease is difficult to diagnose and manage, even for the most experienced ophthalmologists. And the challenges are much worse in remote corners of the world that have limited access to ophthalmic and neonatal care.

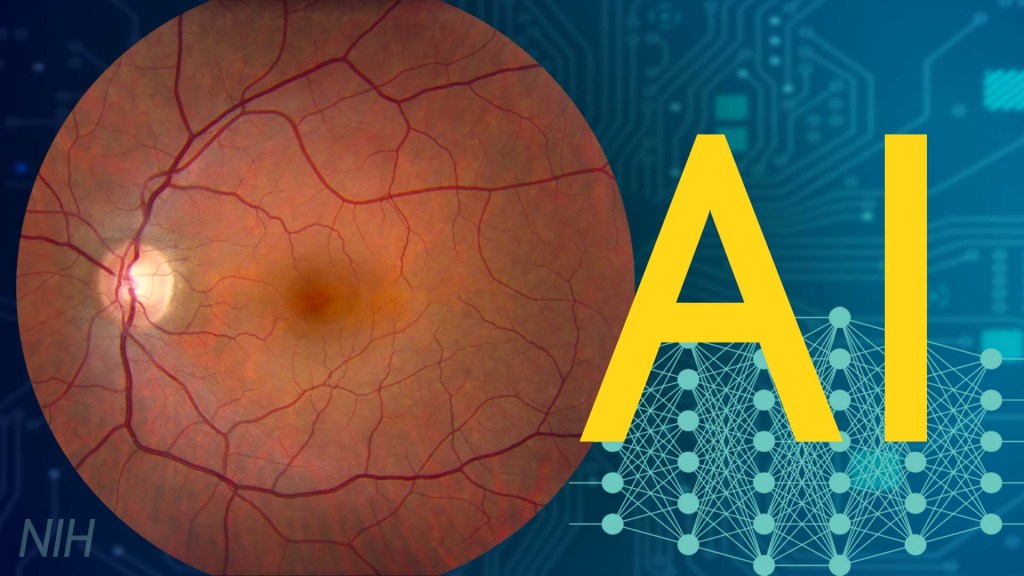

Artificial intelligence (AI) is helping bridge these gaps. Prior to my tenure as National Eye Institute (NEI) director, I helped develop a system called i-ROP Deep Learning (i-ROP DL), which automates the identification of ROP. In essence, we trained a computer to identify subtle abnormalities in retinal blood vessels from thousands of images of premature infant retinas. Strikingly, the i-ROP DL artificial intelligence system outperformed even international ROP experts [1]. This has enormous potential to improve the quality and delivery of eye care to premature infants worldwide.

Of course, the promise of medical artificial intelligence extends far beyond ROP. In 2018, the FDA approved the first autonomous AI-based diagnostic tool in any field of medicine [2]. Called IDx-DR, the system streamlines screening for diabetic retinopathy (DR), and its results require no interpretation by a doctor. DR occurs when blood vessels in the retina grow irregularly, bleed, and potentially cause blindness. About 34 million people in the U.S. have diabetes, and each is at risk for DR.

As with ROP, early diagnosis and intervention is crucial to preventing vision loss to DR. The American Diabetes Association recommends people with diabetes see an eye care provider annually to have their retinas examined for signs of DR. Yet fewer than 50 percent of Americans with diabetes receive these annual eye exams.

The IDx-DR system was conceived by Michael Abramoff, an ophthalmologist and AI expert at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. With NEI funding, Abramoff used deep learning to design a system for use in a primary-care medical setting. A technician with minimal ophthalmology training can use the IDx-DR system to scan a patient’s retinas and get results indicating whether a patient should be sent to an eye specialist for follow-up evaluation or to return for another scan in 12 months.

Many other methodological innovations in AI have occurred in ophthalmology. That’s because imaging is so crucial to disease diagnosis and clinical outcome data are so readily available. As a result, AI-based diagnostic systems are in development for many other eye diseases, including cataract, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and glaucoma.

Rapid advances in AI are occurring in other medical fields, such as radiology, cardiology, and dermatology. But disease diagnosis is just one of many applications for AI. Neurobiologists are using AI to answer questions about retinal and brain circuitry, disease modeling, microsurgical devices, and drug discovery.

If it sounds too good to be true, it may be. There’s a lot of work that remains to be done. Significant challenges to AI utilization in science and medicine persist. For example, researchers from the University of Washington, Seattle, last year tested seven AI-based screening algorithms that were designed to detect DR. They found under real-world conditions that only one outperformed human screeners [3]. A key problem is these AI algorithms need to be trained with more diverse images and data, including a wider range of races, ethnicities, and populations—as well as different types of cameras.

How do we address these gaps in knowledge? We’ll need larger datasets, a collaborative culture of sharing data and software libraries, broader validation studies, and algorithms to address health inequities and to avoid bias. The NIH Common Fund’s Bridge to Artificial Intelligence (Bridge2AI) project and NIH’s Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Consortium to Advance Health Equity and Researcher Diversity (AIM-AHEAD) Program project will be major steps toward addressing those gaps.

So, yes—AI is getting smarter. But harnessing its full power will rely on scientists and clinicians getting smarter, too.

References:

[1] Automated diagnosis of plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity using deep convolutional neural networks. Brown JM, Campbell JP, Beers A, Chang K, Ostmo S, Chan RVP, Dy J, Erdogmus D, Ioannidis S, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Chiang MF; Imaging and Informatics in Retinopathy of Prematurity (i-ROP) Research Consortium. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018 Jul 1;136(7):803-810.

[2] FDA permits marketing of artificial intelligence-based device to detect certain diabetes-related eye problems. Food and Drug Administration. April 11, 2018.

[3] Multicenter, head-to-head, real-world validation study of seven automated artificial intelligence diabetic retinopathy screening systems. Lee AY, Yanagihara RT, Lee CS, Blazes M, Jung HC, Chee YE, Gencarella MD, Gee H, Maa AY, Cockerham GC, Lynch M, Boyko EJ. Diabetes Care. 2021 May;44(5):1168-1175.

Links:

Retinopathy of Prematurity (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Diabetic Eye Disease (NEI)

Michael Abramoff (University of Iowa, Iowa City)

Bridge to Artificial Intelligence (Common Fund/NIH)

[Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s institutes and centers to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog as a way to highlight some of the cool science that they support and conduct. This is the second in the series of NIH institute and center guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.]

New Director for NEI

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Singing A Fun Farewell Song

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Best Wishes to Paul Sieving

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Studying Color Vision in a Dish

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Eldred et al., Science

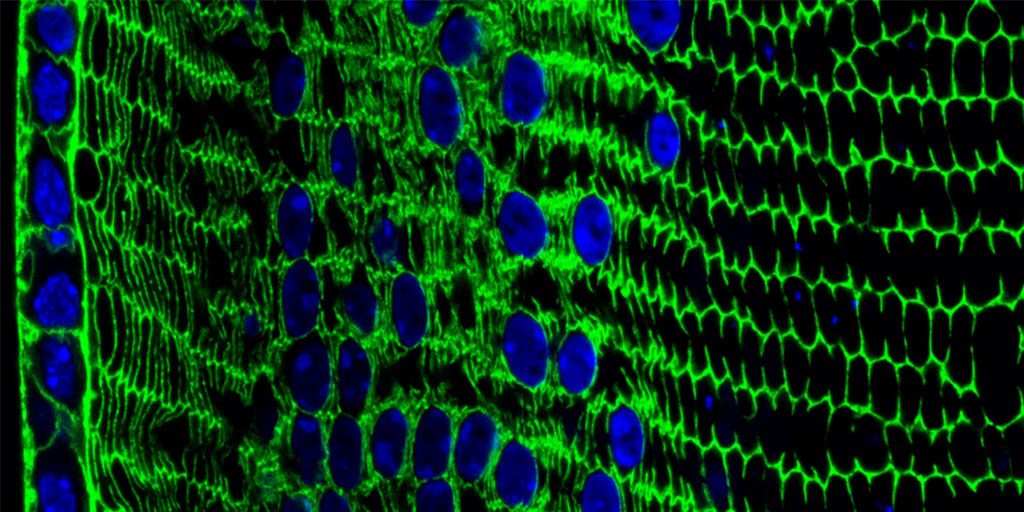

Researchers can now grow miniature versions of the human retina—the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye—right in a lab dish. While most “retina-in-a-dish” research is focused on finding cures for potentially blinding diseases, these organoids are also providing new insights into color vision.

Our ability to view the world in all of its rich and varied colors starts with the retina’s light-absorbing cone cells. In this image of a retinal organoid, you see cone cells (blue and green). Those labelled with blue produce a visual pigment that allows us to see the color blue, while those labelled green make visual pigments that let us see green or red. The cells that are labeled with red show the highly sensitive rod cells, which aren’t involved in color vision, but are very important for detecting motion and seeing at night.

Lens Crafting

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Salma Muhammad Al Saai, Salil Lachke, University of Delaware, Newark

Live long enough, and there’s a good chance that you will develop a cataract, a clouding of the eye’s lens that impairs vision. Currently, U.S. eye surgeons perform about 3 million operations a year to swap out those clouded lenses with clear, artificial ones [1]. But wouldn’t it be great if we could develop non-surgical ways of preventing, slowing, or even reversing the growth of cataracts? This image, from the lab of NIH-grantee Salil Lachke at the University of Delaware, Newark, is part of an effort to do just that.

Here you can see the process of lens development at work in a tissue cross-section from an adult mouse. In mice, as in people, a single layer of stem-like epithelial cells (far left, blue/green) gives rise to specialized lens cells (middle, blue/green) throughout life. The new cells initially resemble their progenitor cells, displaying nuclei (blue) and the cytoskeletal protein actin (green). But soon these cells will produce vast amounts of water-soluble proteins, called crystallins, to enhance their transparency, while gradually degrading their nuclei to eliminate light-scattering bulk. What remains are fully differentiated, enucleated, non-replicating lens fiber cells (right, green), which refract light onto the retina at the back of the eye.

Creative Minds: Reprogramming the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Neuronal circuits in the mouse retina. Cone photoreceptors (red) enable color vision; bipolar neurons (magenta) relay information further along the circuit; and a subtype of bipolar neuron (green) helps process signals sensed by other photoreceptors in dim light.

Credit: Brian Liu and Melanie Samuel, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

When most people think of reprogramming something, they probably think of writing code for a computer or typing commands into their smartphone. Melanie Samuel thinks of brain circuits, the networks of interconnected neurons that allow different parts of the brain to work together in processing information.

Samuel, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wants to learn to reprogram the connections, or synapses, of brain circuits that function less well in aging and disease and limit our memory and ability to learn. She has received a 2016 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to decipher the molecular cues that encourage the repair of damaged synapses or enable neurons to form new connections with other neurons. Because extensive synapse loss is central to most degenerative brain diseases, Samuel’s reprogramming efforts could help point the way to preventing or correcting wiring defects before they advance to serious and potentially irreversible cognitive problems.

Snapshots of Life: A Colorful Look Inside the Retina

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Amy Robinson, Alex Norton, William Silversmith, Jinseop Kim, Kisuk Lee, Aleks Zlasteski, Matt Green, Matthew Balkam, Rachel Prentki, Marissa Sorek, Celia David, Devon Jones, and Doug Bland, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA; Sebastian Seung, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ

This eerie scene might bring back memories of the computer-generated alien war machines from Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds thriller. But what you’re seeing is a computer-generated depiction of a quite different world—the world inside the retina, the light-sensitive tissue that lines the back of the eye. The stilt-legged “creatures” are actually ganglion nerve cells, and what appears to be their long “noses” are fibers that will eventually converge to form the optic nerve that relays visual signals to the brain. The dense, multi-colored mat near the bottom of the image is a region where the ganglia and other types of retinal cells interact to convey visual information.

What I find particularly interesting about this image is that it was produced through the joint efforts of people who played EyeWire, an internet crowdsourcing game developed in the lab of computational neuroscientist Sebastian Seung, now at Princeton University in New Jersey. Seung and his colleagues created EyeWire using a series of high-resolution microscopic images of the mouse retina, which were digitized into 3D cubes containing dense skeins of branching nerve fibers. It’s at this point where the crowdsourcing came in. Online gamers—most of whom aren’t scientists— volunteered for a challenge that involved mapping the 3D structure of individual nerve cells within these 3D cubes. Players literally colored-in the interiors of the cells and progressively traced their long extensions across the image to distinguish them from their neighbors. Sounds easy, but the branches are exceedingly thin and difficult to follow.

Next Page