hearing

A Potential New Way to Prevent Noise-Induced Hearing Loss: Trapping Excess Zinc

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

Hearing loss is a pervasive problem, affecting one in eight people aged 12 and up in the U.S.1 While hearing loss has multiple causes, an important one for millions of people is exposure to loud noises, which can lead to gradual hearing loss, or people can lose their hearing all at once. The only methods used to prevent noise-induced hearing loss today are avoiding loud noises altogether or wearing earplugs or other protective devices during loud activities. But findings from an intriguing new NIH-supported study exploring the underlying causes of this form of hearing loss suggest it may be possible to protect hearing in a different way: with treatments targeting excess and damaging levels of zinc in the inner ear.

The new findings, reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, come from a team led by Thanos Tzounopoulos, Amantha Thathiah, and Chris Cunningham, at the University of Pittsburgh.2 The research team is focused on understanding how hearing works, as well as developing ways to treat hearing loss and tinnitus (the perception of sound, like ringing or buzzing, that doesn’t have an external source), which both can arise from loud noises.

Previous studies have shown that traumatic noises of varying durations and intensities can lead to different types of damage to cells in the cochlea, the fluid-filled cavity in the inner ear that plays an essential role in hearing. For instance, in mouse studies, noise equivalent to a blasting rock concert caused the loss of tiny sound-detecting hair cells and essential supporting cells in the cochlea, leading to hearing loss. Milder noises comparable to the sound of a hand drill can lead to subtler hearing loss, as essential connections, or synapses, between hair cells and sensory neurons are lost.

To better understand why this happens, the research team wanted to investigate the underlying cellular- and molecular-level events and signals responsible for inner ear damage and irreversible hearing loss caused by loud sounds. They looked to zinc, an essential mineral in our diets that plays many important roles in the body. Interestingly, zinc concentrations in the inner ear are highest of any organ or tissue in the body. But, despite this, the role of zinc in the cochlea and its effects on hearing and hearing loss hadn’t been studied in detail.

Most zinc in the body—about 90%—is bound to proteins. But the researchers were interested in the approximately 10% of zinc that’s free-floating, due to its important role in signaling in the brain and other parts of the nervous system. They wanted to find out what happens to the high concentrations of zinc in the mouse cochlea after traumatic levels of noise, and whether targeting zinc might influence inner ear damage associated with hearing loss.

The researchers found that, hours after mice were exposed to loud noise, zinc levels in the inner ear spiked and were dysregulated in the hair cells and in key parts of the cochlea, with significant changes to their location inside cells. Those changes in zinc were associated with cellular damage and disrupted communication between sensory cells in the inner ear.

The good news is that this discovery suggested a possible solution: inner ear damage and hearing loss might be averted by targeting excess zinc. And their subsequent findings suggest that it works. Studies in mice that were treated with a slow-releasing compound in the inner ear were protected from noise-induced damage and associated hearing loss. The treatment involves a chemical compound known as a zinc chelating agent, which binds and traps excess free zinc, thus limiting cochlear damage and hearing loss.

Will this strategy work in people? We don’t know yet. However, the researchers report that they’re planning to pursue preclinical safety studies of the new treatment approach. Their hope is to one day make a zinc-targeted treatment readily available to protect against noise-induced hearing loss. But, for now, the best way to protect your hearing while working with noisy power tools or attending a rock concert is to remember your ear protection.

References:

[1] Quick Statistics About Hearing. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

[2] Bizup B, et al. Cochlear zinc signaling dysregulation is associated with noise-induced hearing loss, and zinc chelation enhances cochlear recovery. PNAS. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2310561121 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

How the Brain Differentiates the ‘Click,’ ‘Crack,’ or ‘Thud’ of Everyday Tasks

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

If you’ve been staying up late to watch the World Series, you probably spent those nine innings hoping for superstars Bryce Harper or José Altuve to square up a fastball and send it sailing out of the yard. Long-time baseball fans like me can distinguish immediately the loud crack of a home-run swing from the dull thud of a weak grounder.

Our brains have such a fascinating ability to discern “right” sounds from “wrong” ones in just an instant. This applies not only in baseball, but in the things that we do throughout the day, whether it’s hitting the right note on a musical instrument or pushing the car door just enough to click it shut without slamming.

Now, an NIH-funded team of neuroscientists has discovered what happens in the brain when one hears an expected or “right” sound versus a “wrong” one after completing a task. It turns out that the mammalian brain is remarkably good at predicting both when a sound should happen and what it ideally ought to sound like. Any notable mismatch between that expectation and the feedback, and the hearing center of the brain reacts.

It may seem intuitive that humans and other animals have this auditory ability, but researchers didn’t know how neurons in the brain’s auditory cortex, where sound is processed, make these snap judgements to learn complex tasks. In the study published in the journal Current Biology, David Schneider, New York University, New York, set out to understand how this familiar experience really works.

To do it, Schneider and colleagues, including postdoctoral fellow Nicholas Audette, looked to mice. They are a lot easier to study in the lab than humans and, while their brains aren’t miniature versions of our own, our sensory systems share many fundamental similarities because we are both mammals.

Of course, mice don’t go around hitting home runs or opening and closing doors. So, the researchers’ first step was training the animals to complete a task akin to closing the car door. To do it, they trained the animals to push a lever with their paws in just the right way to receive a reward. They also played a distinctive tone each time the lever reached that perfect position.

After making thousands of attempts and hearing the associated sound, the mice knew just what to do—and what it should sound like when they did it right. Their studies showed that, when the researchers removed the sound, played the wrong sound, or played the correct sound at the wrong time, the mice took notice and adjusted their actions, just as you might do if you pushed a car door shut and the resulting click wasn’t right.

To find out how neurons in the auditory cortex responded to produce the observed behaviors, Schneider’s team also recorded brain activity. Intriguingly, they found that auditory neurons hardly responded when a mouse pushed the lever and heard the sound they’d learned to expect. It was only when something about the sound was “off” that their auditory neurons suddenly crackled with activity.

As the researchers explained, it seems from these studies that the mammalian auditory cortex responds not to the sounds themselves but to how those sounds match up to, or violate, expectations. When the researchers canceled the sound altogether, as might happen if you didn’t push a car door hard enough to produce the familiar click shut, activity within a select group of auditory neurons spiked right as they should have heard the sound.

Schneider’s team notes that the same brain areas and circuitry that predict and process self-generated sounds in everyday tasks also play a role in conditions such as schizophrenia, in which people may hear voices or other sounds that aren’t there. The team hopes their studies will help to explain what goes wrong—and perhaps how to help—in schizophrenia and other neural disorders. Perhaps they’ll also learn more about what goes through the healthy brain when anticipating the satisfying click of a closed door or the loud crack of a World Series home run.

Reference:

[1] Precise movement-based predictions in the mouse auditory cortex. Audette NJ, Zhou WX, Chioma A, Schneider DM. Curr Biology. 2022 Oct 24.

Links:

How Do We Hear? (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders/NIH)

Schizophrenia (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

David Schneider (New York University, New York)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Advancing Access to Hearing Health Care

Posted on by Debara L. Tucci, M.D., M.S., M.B.A., National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

By 2050, the World Health Organization estimates that more than 700 million people—or one in every 10 people around the globe—will have disabling hearing loss. In the United States alone, hearing loss affects an estimated 30 million people [1]. Hearing loss can be frustrating, isolating, and even dangerous. It is also associated with dementia, depression, anxiety, reduced mobility, and falls.

Although hearing technologies, such as hearing aids, have improved, not everyone has equal access to these advancements. In fact, though hearing aids and other assistive devices can significantly improve quality of life, only one in four U.S. adults who could benefit from these devices has ever used one. Why? People commonly report encountering economic barriers, such as the high cost of hearing aids and limited access to hearing health care. For some, the reasons are more personal. They may not believe that hearing aids are effective, or they may worry about a perceived negative association with aging. [2].

As the lead federal agency supporting research initiatives to prevent, detect, and treat hearing loss, NIH’s National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) conducts and funds research that identifies ways to break down barriers to hearing health care. Decades of NIDCD research informed a recent landmark announcement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) creating a new category of over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids. When the regulation takes effect (expected in 2022), millions of people who have trouble hearing will be able to purchase less expensive hearing aids without a medical exam, prescription, or fitting by an audiologist.

This exciting development has been on the horizon at NIDCD for some time. Back in 2009, NIDCD’s Working Group on Accessible and Affordable Hearing Health Care for Adults with Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss created a blueprint for research priorities.

The working group’s blueprint led to NIDCD funding of more than 60 research projects spanning the landscape of accessible and affordable hearing health care issues. One study showed that people with hearing loss can independently adjust the settings [3] on their hearing devices in response to changing acoustic environments and, when given the ability to control their own hearing aid settings, they were generally more satisfied with the sound of the devices than with the audiologist fit [4].

In 2017, the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial comparing an over-the-counter delivery model [5] of hearing aids with traditional fitting by an audiologist also found that hearing aid users in both groups reported similar benefits. A 2019 follow-up study [6] confirmed these results, supporting the viability of a direct-to-consumer service delivery model. A small-business research grant funded by NIDCD led to the first FDA-approved self-fitting hearing aid.

Meanwhile, in 2016, NIDCD co-sponsored a consensus report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). The report, Hearing Health Care for Adults: Priorities for Improving Access and Affordability, which was developed by an independent expert panel, recommended that the FDA create and regulate a new category of over-the-counter hearing devices to improve access to affordable hearing aids for adults with perceived mild-to-moderate hearing loss. These devices will not be intended for children or for adults with more severe hearing loss.

In sum, this targeted portfolio of NIDCD-funded research—together with the research blueprint and the NASEM consensus report—provided a critical foundation for the 2021 FDA rule creating the new class of OTC hearing aids. As a result of these research and policy efforts, this FDA rule will make some types of hearing aids less expensive and easier to obtain, potentially improving the health, safety, and well-being of millions of Americans.

Transforming hearing health care for adults in the U.S. remains a public health priority. The NIH applauds the scientists who provided critical evidence leading to the new category of hearing aids, and NIDCD encourages them to redouble their efforts. Gaps in hearing health care access remain to be closed.

The NIDCD actively solicits applications for research projects to fill these gaps and continue identifying barriers to care and ways to improve access. The NIDCD will also continue to help the public understand the importance of hearing health care with resources on its website, such as Hearing: A Gateway to Our World video and the Adult Hearing Health Care webpage.

References:

[1] Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Lin F, Niparko J, Ferrucci L. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Nov 14;171(20):1851-1852.

[2] Research drives more accessible, affordable hearing care. Tucci DL, King K. The Hearing Journal. May 2020.

[3] A “Goldilocks” approach to hearing aid self-fitting: Ear-canal output and speech intelligibility index. Mackersie C, Boothroyd A, Lithgow, A. Ear and Hearing. Jan 2019.

[4] Self-adjusted amplification parameters produce large between-subject variability and preserve speech intelligibility. Nelson PB, Perry TT, Gregan M, VanTasell, D. Trends in Hearing. 7 Sep 2018.

[5] The effects of service-delivery model and purchase price on hearing-aid outcomes in older adults: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Humes LE, Rogers SE, Quigley TM, Main AK, Kinney DL, Herring C. American Journal of Audiology. 1 Mar 2017.

[6] A follow-up clinical trial evaluating the consumer-decides service delivery model. Humes LE, Kinney DL, Main AK, Rogers SE. American Journal of Audiology. 15 Mar 2019.

Links:

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) (NIH)

Funded Research Projects on Accessible and Affordable Hearing Health Care (NIDCD)

Adult Hearing Health Care (NIDCD)

[Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the ninth in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.]

Testifying Before House Subcommittee

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

On May 11, I was pleased to appear before the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies to discuss NIH’s budget request for Fiscal Year 2023. Joining me (left to right) were leaders of several NIH institutes: Nora Volkow, National Institute on Drug Abuse; Tony Fauci, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Diana Bianchi, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Doug Lowy, National Cancer Institute; and Gary Gibbons, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

A Nose for Science

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Our nose does a lot more than take in oxygen, smell, and sometimes sniffle. This complex organ also helps us taste and, as many of us notice during spring allergy season when our noses get stuffy, it even provides some important anatomic features to enable us to speak clearly.

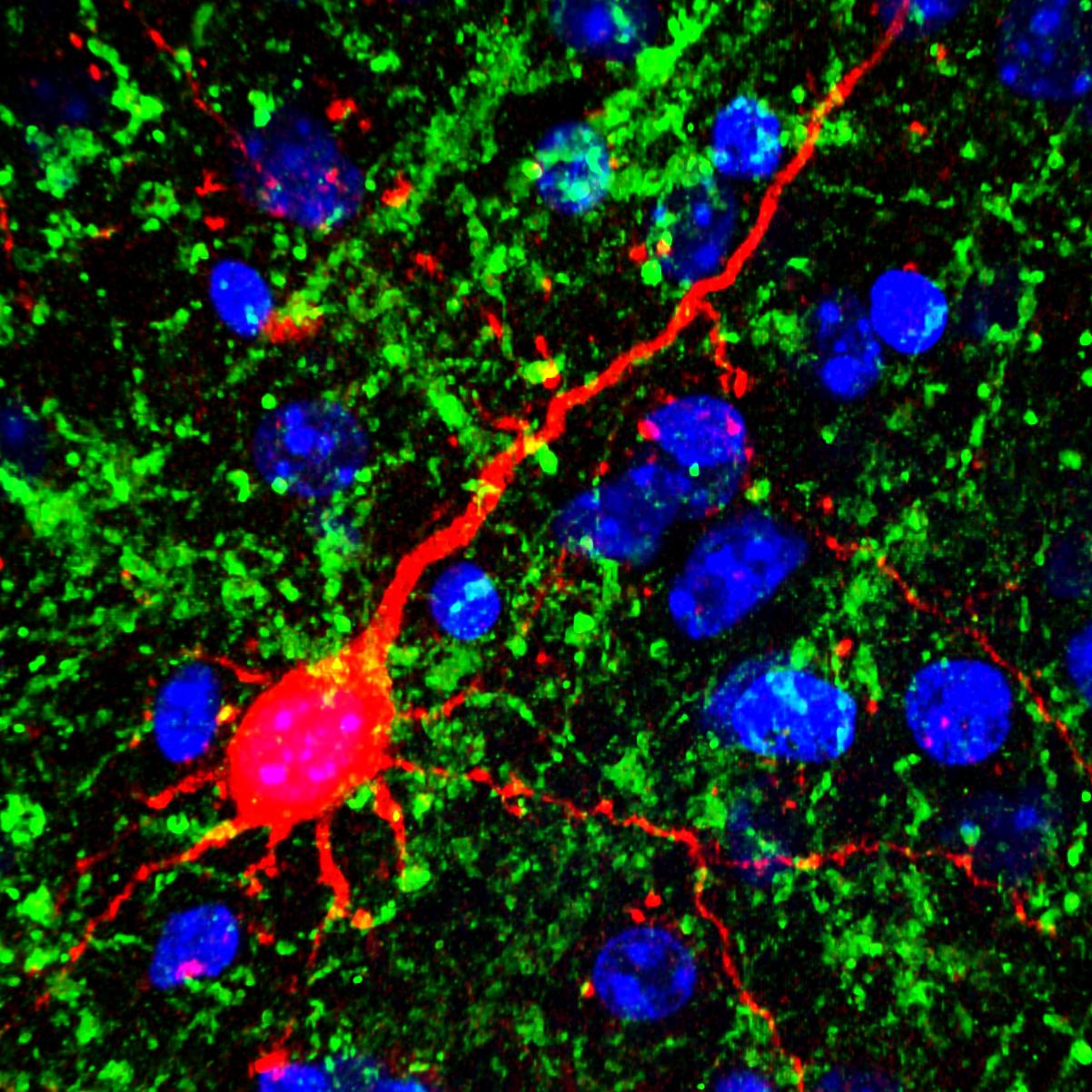

This colorful, almost psychedelic image shows the entire olfactory epithelium, or “smell center,” (green) inside the nasal cavity of a newborn mouse. The olfactory epithelium drapes over the interior walls of the nasal cavity and its curvy bony parts (red). Every cell in the nose contains DNA (blue).

The olfactory epithelium detects odorant molecules in the air, providing a sense of smell. In humans, the nose has about 400 types of scent receptors, and they can detect at least 1 trillion different odors [1].

But this is more than just a cool image captured by graduate student Lu Yang, who works with David Ornitz at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. The two discovered a new type of progenitor cell, called a FEP cell, that has the capacity to generate the entire smell center [2]. Progenitor cells are made by stem cells. But they are capable of multiplying and producing various cells of a particular lineage that serve as the workforce for specialized tissues, such as the olfactory epithelium.

Yang and Ornitz also discovered that the FEP cells crank out a molecule, called FGF20, that controls the growth of the bony parts in the nasal cavity. This seems to regulate the size of the olfactory system, which has fascinating implications for understanding how many mammals possess a keener sense of smell than humans.

But it turns out that FGF20 does a lot more than control smell. While working in Ornitz’s lab as a postdoc, Sung-Ho Huh, now an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, discovered that FGF20 helps form the cochlea [3]. This inner-ear region allows us to hear, and mice born without FGF20 are deaf. Other studies show that FGF20 is important for development of the kidney, teeth, mammary gland, and of specific types of hair [4-7]. Clearly, this indicates multi-tasking can be a key feature of a protein, not a trivial glitch.

The image was one of the winners in the 2018 BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition, sponsored by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB). Its vibrant colors help to show the basics of smell, and remind us that every scientific picture tells a story.

References:

[1] Humans can discriminate more than 1 trillion olfactory stimuli. Bushdid C1, Magnasco MO, Vosshall LB, Keller A. Science. 2014 Mar 21;343(6177):1370-1372.

[2] FGF20-Expressing, Wnt-Responsive Olfactory Epithelial Progenitors Regulate Underlying Turbinate Growth to Optimize Surface Area. Yang LM, Huh SH, Ornitz DM. Dev Cell. 2018;46(5):564-580.

[3] Differentiation of the lateral compartment of the cochlea requires a temporally restricted FGF20 signal. Huh SH, Jones J, Warchol ME, Ornitz DM. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(1):e1001231.

[4] FGF9 and FGF20 maintain the stemness of nephron progenitors in mice and man. Barak H, Huh SH, Chen S, Jeanpierre C, Martinovic J, Parisot M, Bole-Feysot C, Nitschke P, Salomon R, Antignac C, Ornitz DM, Kopan R. Dev. Cell. 2012;22(6):1191-1207

[5] Ectodysplasin target gene Fgf20 regulates mammary bud growth and ductal invasion and branching during puberty. Elo T, Lindfors PH, Lan Q, Voutilainen M, Trela E, Ohlsson C, Huh SH, Ornitz DM, Poutanen M, Howard BA, Mikkola ML. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5049

[6] Ectodysplasin regulates activator-inhibitor balance in murine tooth development through Fgf20 signaling. D Haara O, Harjunmaa E, Lindfors PH, Huh SH, Fliniaux I, Aberg T, Jernvall J, Ornitz DM, Mikkola ML, Thesleff I. Development. 2012;139(17):3189-3199.

[7] Fgf20 governs formation of primary and secondary dermal condensations in developing hair follicles. Huh SH, Närhi K, Lindfors PH, Häärä O, Yang L, Ornitz DM, Mikkola ML. Genes Dev. 2013;27(4):450-458.

Links:

Taste and Smell (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders/NIH)

Ornitz Lab, (Washington University, St. Louis)

Huh Lab, (University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha)

BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition, (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Snapshots of Life: Hardwired to Sense Food Texture

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s a problem that parents know all too well: a child won’t eat because their oatmeal is too slimy or a slice of apple is too hard. Is the kid just being finicky? Or is there a biological basis for disliking food based on its texture? This image, showing the tongue (red) of a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), provides some of the first evidence that biology could indeed play a role [1].

The image shows a newly discovered mechanosensory nerve cell (green), which is called md-L, short for multidendritic neuron in the labellum. When the fly extends its tongue to eat, the hair bristles (short red lines) on its surface bend in proportion to the consistency of the food. If a bristle is bent hard enough, the force is detected at its base by one of the arms of an md-L neuron. In response, the arm shoots off an electrical signal that’s relayed to the central part of the neuron and onward to the brain via the outgoing informational arm, or axon.

LabTV: Curious About Genetics of Deafness

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

What do Miami, music, and genetic research have in common? They are all central to the life of Joseph Foster, the young researcher who’s in the spotlight for our next installment of LabTV.

What do Miami, music, and genetic research have in common? They are all central to the life of Joseph Foster, the young researcher who’s in the spotlight for our next installment of LabTV.

Foster, a research associate in Mustafa Tekin’s lab at the University of Miami’s Hussman Institute for Human Genomics, is involved in the hunt for the remaining genes responsible for congenital forms of deafness.This area of research is a good fit for Foster. Not only does he have a keen interest in genetic diseases (a close family member was born with cystic fibrosis), he’s a musician with a deep appreciation of the gift of hearing—loving to play the saxophone in his free time.

Creative Minds: A Baby’s Eye View of Language Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you are a fan of wildlife shows, you’ve probably seen those tiny video cameras rigged to animals in the wild that provide a sneak peek into their secret domains. But not all research cams are mounted on creatures with fur, feathers, or fins. One of NIH’s 2014 Early Independence Award winners has developed a baby-friendly, head-mounted camera system (shown above) that captures the world from an infant’s perspective and explores one of our most human, but still imperfectly understood, traits: language.

If you are a fan of wildlife shows, you’ve probably seen those tiny video cameras rigged to animals in the wild that provide a sneak peek into their secret domains. But not all research cams are mounted on creatures with fur, feathers, or fins. One of NIH’s 2014 Early Independence Award winners has developed a baby-friendly, head-mounted camera system (shown above) that captures the world from an infant’s perspective and explores one of our most human, but still imperfectly understood, traits: language.

Elika Bergelson, a young researcher at the University of Rochester in New York, wants to know exactly how and when infants acquire the ability to understand spoken words. Using innovative camera gear and other investigative tools, she hopes to refine current thinking about the natural timeline for language acquisition. Bergelson also hopes her work will pay off in a firmer theoretical foundation to help clinicians assess children with poor verbal skills or with neurodevelopmental conditions that impair information processing, such as autism spectrum disorders.

Vision Loss Boosts Auditory Perception

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Emily Petrus, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

Many people with vision loss—including such gifted musicians as the late Doc Watson (my favorite guitar picker), Stevie Wonder, Andrea Bocelli, and the Blind Boys of Alabama—are thought to have supersensitive hearing. They are often much better at discriminating pitch, locating the origin of sounds, and hearing softer tones than people who can see. Now, a new animal study suggests that even a relatively brief period of simulated blindness may have the power to enhance hearing among those with normal vision.

In the study, NIH-funded researchers at the University of Maryland in College Park, and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, found that when they kept adult mice in complete darkness for one week, the animals’ ability to hear significantly improved [1]. What’s more, when they examined the animals’ brains, the researchers detected changes in the connections among neurons in the part of the brain where sound is processed, the auditory cortex.

Next Page