inflammatory bowel disease

Millions of Single-Cell Analyses Yield Most Comprehensive Human Cell Atlas Yet

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

There are 37 trillion or so cells in our bodies that work together to give us life. But it may surprise you that we still haven’t put a good number on how many distinct cell types there are within those trillions of cells.

That’s why in 2016, a team of researchers from around the globe launched a historic project called the Human Cell Atlas (HCA) consortium to identify and define the hundreds of presumed distinct cell types in our bodies. Knowing where each cell type resides in the body, and which genes each one turns on or off to create its own unique molecular identity, will revolutionize our studies of human biology and medicine across the board.

Since its launch, the HCA has progressed rapidly. In fact, it has already reached an important milestone with the recent publication in the journal Science of four studies that, together, comprise the first multi-tissue drafts of the human cell atlas. This draft, based on analyses of millions of cells, defines more than 500 different cell types in more than 30 human tissues. A second draft, with even finer definition, is already in the works.

Making the HCA possible are recent technological advances in RNA sequencing. RNA sequencing is a topic that’s been mentioned frequently on this blog in a range of research areas, from neuroscience to skin rashes. Researchers use it to detect and analyze all the messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules in a biological sample, in this case individual human cells from a wide range of tissues, organs, and individuals who voluntarily donated their tissues.

By quantifying these RNA messages, researchers can capture the thousands of genes that any given cell actively expresses at any one time. These precise gene expression profiles can be used to catalogue cells from throughout the body and understand the important similarities and differences among them.

In one of the published studies, funded in part by the NIH, a team co-led by Aviv Regev, a founding co-chair of the consortium at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, established a framework for multi-tissue human cell atlases [1]. (Regev is now on leave from the Broad Institute and MIT and has recently moved to Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, CA.)

Among its many advances, Regev’s team optimized single-cell RNA sequencing for use on cell nuclei isolated from frozen tissue. This technological advance paved the way for single-cell analyses of the vast numbers of samples that are stored in research collections and freezers all around the world.

Using their new pipeline, Regev and team built an atlas including more than 200,000 single-cell RNA sequence profiles from eight tissue types collected from 16 individuals. These samples were archived earlier by NIH’s Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. The team’s data revealed unexpected differences among cell types but surprising similarities, too.

For example, they found that genetic profiles seen in muscle cells were also present in connective tissue cells in the lungs. Using novel machine learning approaches to help make sense of their data, they’ve linked the cells in their atlases with thousands of genetic diseases and traits to identify cell types and genetic profiles that may contribute to a wide range of human conditions.

By cross-referencing 6,000 genes previously implicated in causing specific genetic disorders with their single-cell genetic profiles, they identified new cell types that may play unexpected roles. For instance, they found some non-muscle cells that may play a role in muscular dystrophy, a group of conditions in which muscles progressively weaken. More research will be needed to make sense of these fascinating, but vital, discoveries.

The team also compared genes that are more active in specific cell types to genes with previously identified links to more complex conditions. Again, their data surprised them. They identified new cell types that may play a role in conditions such as heart disease and inflammatory bowel disease.

Two of the other papers, one of which was funded in part by NIH, explored the immune system, especially the similarities and differences among immune cells that reside in specific tissues, such as scavenging macrophages [2,3] This is a critical area of study. Most of our understanding of the immune system comes from immune cells that circulate in the bloodstream, not these resident macrophages and other immune cells.

These immune cell atlases, which are still first drafts, already provide an invaluable resource toward designing new treatments to bolster immune responses, such as vaccines and anti-cancer treatments. They also may have implications for understanding what goes wrong in various autoimmune conditions.

Scientists have been working for more than 150 years to characterize the trillions of cells in our bodies. Thanks to this timely effort and its advances in describing and cataloguing cell types, we now have a much better foundation for understanding these fundamental units of the human body.

But the latest data are just the tip of the iceberg, with vast flows of biological information from throughout the human body surely to be released in the years ahead. And while consortium members continue making history, their hard work to date is freely available to the scientific community to explore critical biological questions with far-reaching implications for human health and disease.

References:

[1] Single-nucleus cross-tissue molecular reference maps toward understanding disease gene function. Eraslan G, Drokhlyansky E, Anand S, Fiskin E, Subramanian A, Segrè AV, Aguet F, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Ardlie KG, Regev A, et al. Science. 2022 May 13;376(6594):eabl4290.

[2] Cross-tissue immune cell analysis reveals tissue-specific features in humans. Domínguez Conde C, Xu C, Jarvis LB, Rainbow DB, Farber DL, Saeb-Parsy K, Jones JL,Teichmann SA, et al. Science. 2022 May 13;376(6594):eabl5197.

[3] Mapping the developing human immune system across organs. Suo C, Dann E, Goh I, Jardine L, Marioni JC, Clatworthy MR, Haniffa M, Teichmann SA, et al. Science. 2022 May 12:eabo0510.

Links:

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Studying Cells (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Regev Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Cancer Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Eye Institute

Fundamental Knowledge of Microbes Shedding New Light on Human Health

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Basic research in biology generates fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems. It is generally impossible to predict exactly where this line of scientific inquiry might lead, but history shows that basic science almost always serves as the foundation for dramatic breakthroughs that advance human health. Indeed, many important medical advances can be traced back to basic research that, at least at the outset, had no clear link at all to human health.

One exciting example of NIH-supported basic research is the Human Microbiome Project (HMP), which began 12 years ago as a quest to use DNA sequencing to identify and characterize the diverse collection of microbes—including trillions of bacteria, fungi, and viruses—that live on and in the healthy human body.

The HMP researchers have subsequently been using those vast troves of fundamental data as a tool to explore how microbial communities interact with human cells to influence health and disease. Today, these explorers are reporting their latest findings in a landmark set of papers in the Nature family of journals. Among other things, these findings shed new light on the microbiome’s role in prediabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and preterm birth. The studies are part of the Integrative Human Microbiome Project.

If you’d like to keep up on the microbiome and other basic research journeys, here’s a good way to do so. Consider signing up for basic research updates from the NIH Director’s Blog and NIH Research Matters. Here’s how to do it: Go to Email Updates, type in your email address, and enter. That’s it. If you’d like to see other update possibilities, including clinical and translational research, hit the “Finish” button to access Subscriber Preferences.

As for the recent microbiome findings, let’s start with the prediabetes study [1]. An estimated 1 in 3 American adults has prediabetes, detected by the presence of higher than normal fasting blood glucose levels. If uncontrolled and untreated, prediabetes can lead to the more-severe type 2 diabetes (T2D) and its many potentially serious side effects [2].

George Weinstock, The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, CT, Michael Snyder, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, and colleagues report that they have assembled a rich new data set covering the complex biology of prediabetes. That includes a comprehensive analysis of the human microbiome in prediabetes.

The data come from monitoring the health of 106 people with and without prediabetes for nearly four years. The researchers met with participants every three months, drawing blood, assessing the gut microbiome, and performing 51 laboratory tests. All this work generated millions of molecular and microbial measurements that provided a unique biological picture of prediabetes.

The picture showed specific interactions between cells and microbes that were different for people who are sensitive to insulin and those whose cells are resistant to it (as is true of many of those with prediabetes). The data also pointed to extensive changes in the microbiome during respiratory viral infections. Those changes showed clear differences in people with and without prediabetes. Some aspects of the immune response also appeared abnormal in people who were prediabetic.

As demonstrated in a landmark NIH study several years ago [2], people with prediabetes can do a lot to reduce their chances of developing T2D, such as exercising, eating healthy, and losing a modest amount of body weight. But this study offers some new leads to define the biological underpinnings of T2D in its earliest stages. These insights potentially point to high value targets for slowing or perhaps stopping the systemic changes that drive the transition from prediabetes to T2D.

The second study features the work of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multi’omics Data team. It’s led by Ramnik Xavier and Curtis Huttenhower, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA. [4]

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an umbrella term for chronic inflammations of the body’s digestive tract, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. These disorders are characterized by remissions and relapses, and the most severe flares can be life-threatening. Xavier, Huttenhower, and team followed 132 people with and without IBD for a year, collecting samples of their gut microbiomes every other week along with biopsies and blood samples for a total of nearly 3,000 samples.

By integrating DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolic analyses, they followed precisely which microbial species were present. They could also track which biochemical functions those microbes were capable of performing, and which functions they actually were performing over the course of the study.

These data now offer the most comprehensive view yet of functional imbalances associated with changes in the microbiome during IBD flares. These data also show how those imbalances may be altered when a person with IBD goes into remission. It’s also noteworthy that participants completed questionnaires on their diet. This dataset is the first to capture associations between diet and the gut microbiome in a relatively large group of people over time.

The evidence showed that the gut microbiomes of people with IBD were significantly less stable than the microbiomes of those without IBD. During IBD activity, the researchers observed increases in certain groups of microbes at the expense of others. Those changes in the microbiome also came with other telltale metabolic and biochemical disruptions along with shifts in the functioning of an individual’s immune system. The shifts, however, were not significantly associated with people taking medications or their social status.

By presenting this comprehensive, “multi-omic” view on the microbiome in IBD, the researchers were able to single out a variety of new host and microbial features that now warrant further study. For example, people with IBD had dramatically lower levels of an unclassified Subdoligranulum species of bacteria compared to people without the condition.

The third study features the work of The Vaginal Microbiome Consortium (VMC). The study represents a collaboration between Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and Global Alliance to Prevent Prematurity and Stillbirth (GAPPS). The VMC study is led by Gregory Buck, Jennifer Fettweis, Jerome Strauss,and Kimberly Jefferson of Virginia Commonwealth and colleagues.

In this study, part of the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative, the team followed up on previous research that suggested a potential link between the composition of the vaginal microbiome and the risk of preterm birth [5]. The team collected various samples from more than 1,500 pregnant women at multiple time points in their pregnancies. The researchers sequenced the complete microbiomes from the vaginal samples of 45 study participants, who gave birth prematurely and 90 case-matched controls who gave birth to full-term babies. Both cases and controls were primarily of African ancestry.

Those data reveal unique microbial signatures early in pregnancy in women who went on to experience a preterm birth. Specifically, women who delivered their babies earlier showed lower levels of Lactobacillus crispatus, a bacterium long associated with health in the female reproductive tract. Those women also had higher levels of several other microbes. The preterm birth-associated signatures also were associated with other inflammatory molecules.

The findings suggest a link between the vaginal microbiome and preterm birth, and raise the possibility that a microbiome test, conducted early in pregnancy, might help to predict a woman’s risk for preterm birth. Even more exciting, this might suggest a possible way to modify the vaginal microbiome to reduce the risk of prematurity in susceptible individuals.

Overall, these landmark HMP studies add to evidence that our microbial inhabitants have important implications for many aspects of our health. We are truly a “superorganism.” In terms of the implications for biomedicine, this is still just the beginning of what is sure to be a very exciting journey.

References:

[1] Longitudinal multi-omics of host-microbe dynamics in prediabetes. Zhou W, Sailani MR, Contrepois K, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Snyder M, et. al. Nature. 2019 May 29.

[2] National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA)

[3] Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group.Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.2015 Nov;3(11):866-875.

[4] Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel disease. Lloyd-Price J, Arze C. Ananthakrishnan AN, Vlamakis H, Xavier RJ, Huttenhower C, et. al. Nature. 2019 May 29.

[5] The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Brooks, JP, Jefferson KK, Strauss JF, Buck GA, et al. Nature Med. 2019 May 29.

Links:

Insulin Resistance & Prediabetes (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Crohn’s Disease (NIDDK/NIH)

Ulcerative colitis (NIDDK/NIH)

Preterm Labor and Birth: Condition Information (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH)

Global Alliance to Prevent Prematurity and Stillbirth (Seattle, WA)

NIH Integrative Human Microbiome Project

NIH Support:

Prediabetes Study: Common Fund; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Institute of Human Genome Research; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study: Common Fund; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Human Genome Research; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Preterm Birth Study: Common Fund; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Creative Minds: Giving Bacteria Needles to Fight Intestinal Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For Salmonella and many other disease-causing bacteria that find their way into our bodies, infection begins with a poke. That’s because these bad bugs are equipped with a needle-like protein filament that punctures the outer membrane of human cells and then, like a syringe, injects dozens of toxic proteins that help them replicate.

Cammie Lesser at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, and her colleagues are now on a mission to bioengineer strains of bacteria that don’t cause disease to make these same syringes, called type III secretion systems. The goal is to use such “good” bacteria to deliver therapeutic molecules, rather than toxins, to human cells. Their first target is the gastrointestinal tract, where they hope to knock out hard-to-beat bacterial infections or to relieve the chronic inflammation that comes with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Creative Minds: New Piece in the Crohn’s Disease Puzzle?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Gwendalyn Randolph

Back in the early 1930s, Burrill Crohn, a gastroenterologist in New York, decided to examine intestinal tissue biopsies from some of his patients who were suffering from severe bowel problems. It turns out that 14 showed signs of severe inflammation and structural damage in the lower part of the small intestine. As Crohn later wrote a medical colleague, “I have discovered, I believe, a new intestinal disease …” [1]

More than eight decades later, the precise cause of this disorder, which is now called Crohn’s disease, remains a mystery. Researchers have uncovered numerous genes, microbes, immunologic abnormalities, and other factors that likely contribute to the condition, estimated to affect hundreds of thousands of Americans and many more worldwide [2]. But none of these discoveries alone appears sufficient to trigger the uncontrolled inflammation and pathology of Crohn’s disease.

Other critical pieces of the Crohn’s puzzle remain to be found, and Gwendalyn Randolph thinks she might have her eyes on one of them. Randolph, an immunologist at Washington University, St. Louis, suspects that Crohn’s disease and other related conditions, collectively called inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), stems from changes in vessels that carry nutrients, immune cells, and possibly microbial components away from the intestinal wall. To pursue this promising lead, Rudolph has received a 2015 NIH Director’s Pioneer Award.

Manipulating Microbes: New Toolbox for Better Health?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

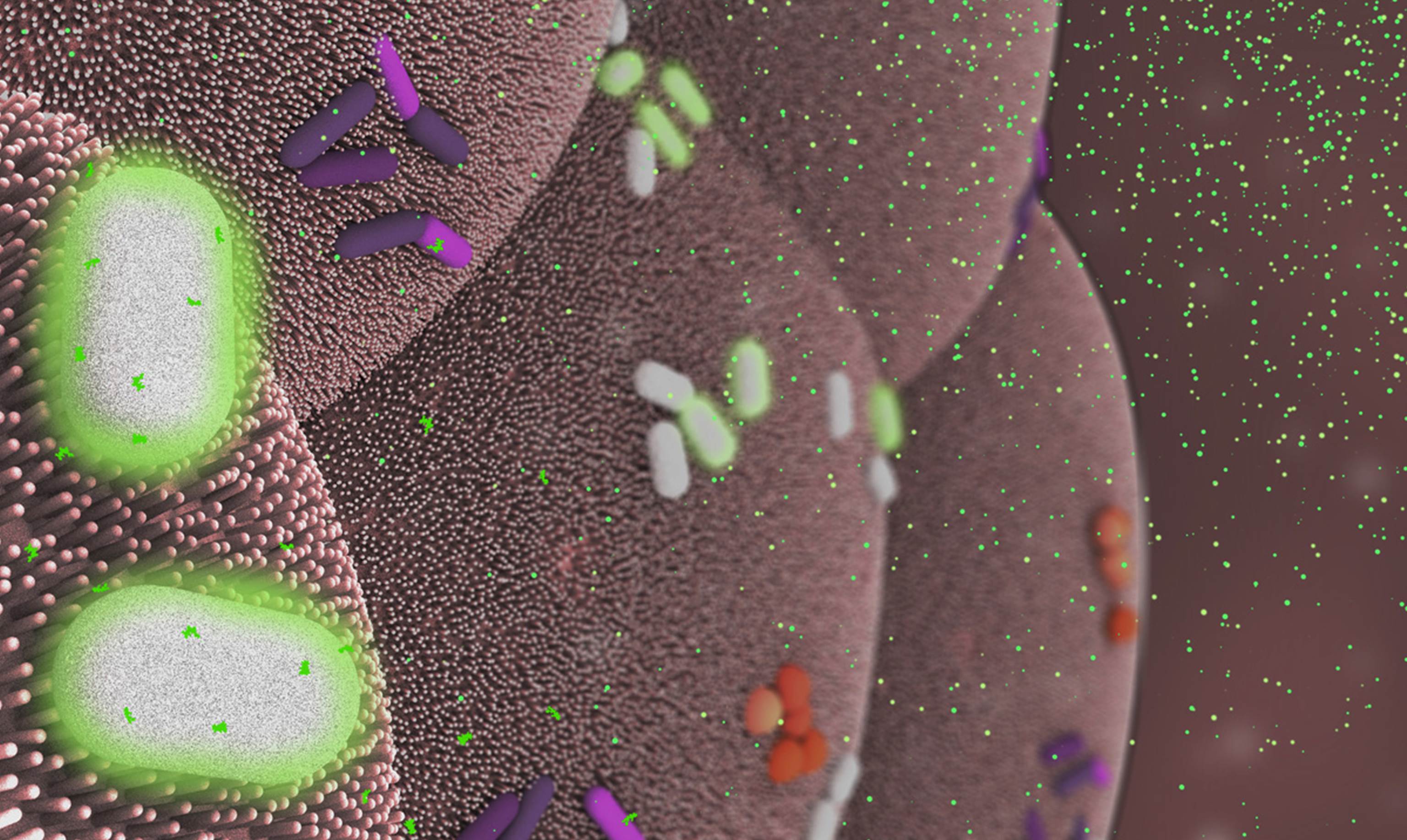

Caption: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (white) living on mammalian cells in the gut (large pink cells coated in microvilli) and being activated by exogenously added compounds (small green dots) to express specific genes, such as those encoding light-generating luciferase proteins (glowing bacteria).

Credit: Janet Iwasa, Broad Visualization Group, MIT Media Lab

When you think about the cells that make up your body, you probably think about the cells in your skin, blood, heart, and other tissues and organs. But the one-celled microbes that live in and on the human body actually outnumber your own cells by a factor of about 10 to 1. Such microbes are especially abundant in the human gut, where some of them play essential roles in digestion, metabolism, immunity, and maybe even your mood and mental health. You are not just an organism. You are a superorganism!

Now imagine for a moment if the microbes that live inside our guts could be engineered to keep tabs on our health, sounding the alarm if something goes wrong and perhaps even acting to fix the problem. Though that may sound like science fiction, an NIH-funded team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, MA, is already working to realize this goal. Most recently, they’ve developed a toolbox of genetic parts that make it possible to program precisely one of the most common bacteria found in the human gut—an achievement that provides a foundation for engineering our collection of microbes, or microbiome, in ways that may treat or prevent disease.