ivacaftor

Dare to Dream: The Long Road to Targeted Therapies for Cystic Fibrosis

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When your world has been touched by a life-threatening disease, it’s hard to spend a lot of time dreaming about the future. But that’s exactly what Jenny, an 8-year-old girl with cystic fibrosis (CF), did 30 years ago upon hearing the news that I and my colleagues in Ann Arbor and Toronto had discovered the gene for CF [1,2]. Her upbeat diary entry, which you can read above, is among the many ways in which people with CF have encouraged researchers on the long and difficult road toward achieving our shared dream of effective, molecularly targeted therapies for one of the nation’s most common potentially fatal recessive genetic diseases, affecting more than 30,000 individuals in the United States [3].

Today, I’m overjoyed to say that this dream finally appears to have come true for about 90 percent of people with CF. In papers in the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet [4,5], two international teams, including researchers partly supported by NIH, report impressive results from phase 3 clinical trials of a triple drug therapy for individuals with CF and at least one copy of Phe508del, the most common CF-causing mutation. And Jenny happens to be among those who now stand to benefit from this major advance.

Now happily married and living in Colorado, Jenny is leading an active life, writing a children’s book and trying to keep up with her daughter Pippa Lou, whom you see with her in the photo above. In a recent email to me, her optimistic outlook continues to shine through: “I have ALWAYS known in my heart that CF will be cured during my lifetime and I have made it my goal to be strong and ready for that day when it comes. None of the advancements in care would be what they are without you.”

But there are a great many more people who need to be recognized and thanked. Such advances were made possible by decades of work involving a vast number of other researchers, many funded by NIH, as well as by more than two decades of visionary and collaborative efforts between the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and Aurora Biosciences (now, Vertex Pharmaceuticals) that built upon that fundamental knowledge of the responsible gene and its protein product. Not only did this innovative approach serve to accelerate the development of therapies for CF, it established a model that may inform efforts to develop therapies for other rare genetic diseases.

To understand how the new triple therapy works, one first needs to understand some things about the protein affected by CF, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR). In healthy people, CFTR serves as a gated channel for chloride ions in the cell membrane, regulating the balance of salt and water in the lungs, pancreas, sweat glands, and other organ systems.

People with the most common CF-causing Phe508del mutation produce a CFTR protein with two serious problems: misfolding that often results in the protein becoming trapped in the cell’s factory production line called the endoplasmic reticulum; and deficient activation of any protein that does manage to reach its proper location in the cell membrane. Consequently, an effective therapy for such people needs to include drugs that can correct the CFTR misfolding, along with those than can activate, or potentiate, the function of CFTR when it reaches the cell membrane.

The new triple combination therapy, which was developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals and recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [6], is elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor (two correctors and one potentiator). This approach builds upon the success of ivacaftor monotherapy, approved by the FDA in 2012 for rare CF-causing mutations; and tezacaftor-ivacaftor dual therapy, approved by the FDA in 2018 for people with two copies of the Phe508del mutation.

Specifically, the final results from two Phase 3 multi-center, randomized clinical trials demonstrated the safety and efficacy of the triple combination therapy for people with either one or two copies of the Phe508del mutation—which represents about 90 percent of people with CF. Patients in both trials experienced striking improvements in a key measure of lung capacity (forced expiratory volume in 1 second) and in sweat chloride levels, which show if the drugs are working throughout the body. In addition, the triple therapy was generally safe and well tolerated, with less than 1 percent of patients discontinuing the treatment due to adverse effects.

This is wonderful news! But let’s be clear—we are not yet at our journey’s end when it comes to realizing the full dream of defeating CF. More work remains to be done to help the approximately 10 percent of CF patients whose mutations result in the production of virtually no CFTR protein, which means there is nothing for current drugs to correct or activate.

Beyond that, wouldn’t it be great if biomedical science could figure out a way to permanently cure CF, perhaps using nonheritable gene editing, so no one needs to take drugs at all? It’s a bold dream, but look how far a little dreaming, plus a lot of hard work, has taken us so far in Jenny’s life.

In closing, I’d like to leave you with the chorus of a song, called “Dare to Dream,” that I wrote shortly after we identified the CF gene. I hope the words inspire not only folks affected by CF, but everyone who is looking to NIH-supported research for healing and hope.

Dare to dream, dare to dream,

All our brothers and sisters breathing free.

Unafraid, our hearts unswayed,

‘Til the story of CF is history.

References:

[1]. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, et al. Science 1989; 245:1059-1065.

[2]. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, et al. Science 1989; 245:1066-73. Erratum in: Science 1989; 245:1437.

[3] Realizing the Dream of Molecularly Targeted Therapies for Cystic Fibrosis. Collins, FS. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 31. [Epub ahead of print]

[4]. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for CF with a Single Phe508del Mutation. Middleton P, Mall M, Drevinek P, et al.N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 31. [Epub ahead of print]

[5] Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Heijerman H, McKone E, Downey D, et al. Lancet. 2019 Oct 31. [Epub ahead of print]

[6] FDA approves new breakthrough therapy for cystic fibrosis. FDA News Release, Oct. 21, 2019.

Links:

Cystic Fibrosis (Genetics Home Reference/National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Research Milestones (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Bethesda, MD)

Wheezie Stevens in “Bubbles Can’t Hold Rain,” by Jennifer K. McGlincy

NIH Support: National, Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Cystic Fibrosis: Keeping the Momentum Going

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

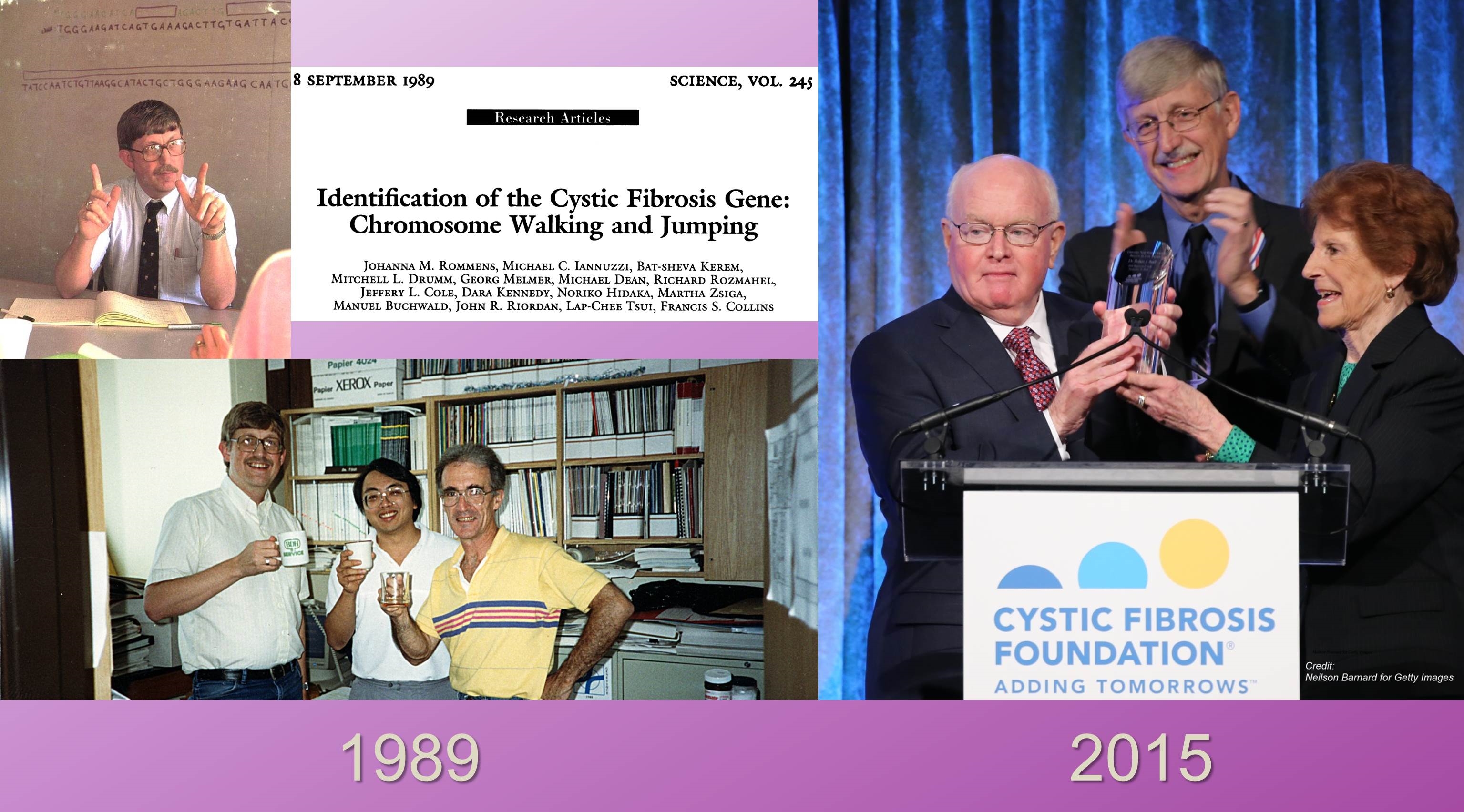

Caption: Lower left, me, Lap-Chee Tsui, and John Riordan celebrating our discovery of the cystic fibrosis gene. Right, Robert J. Beall, me, and Doris Tulcin at a November Cystic Fibrosis Foundation event honoring Dr. Beall.

It’s been more than a quarter-century since my colleagues and I were able to identify the gene responsible for cystic fibrosis (CF), a life-shortening inherited disease that mainly affects the lungs and pancreas [1]. And, at a recent event in New York, I had an opportunity to celebrate how far we’ve come since then in treating CF, as well as to honor a major force behind that progress, Dr. Bob Beall, who has just retired as president and chief executive officer of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of Bob and many others in the public and private sectors to support basic, translational, and clinical research, we today have two therapies from Vertex Pharmaceuticals that are targeted specifically at CF’s underlying molecular cause: ivacaftor (Kalydeco™), approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for people with an uncommon mutation in the CF gene; and the combination ivacaftor-lumacaftor (Orkambi™), approved by the FDA in July for the roughly 50 percent of CF patients with two copies of the most common mutation. Yet more remains to be done before we can truly declare victory. Not only are new therapies needed for people with other CF mutations, but also for those with the common mutation who don’t respond well to Orkambi™. So, the work needs to go on, and I’m encouraged by new findings that suggest a different strategy for helping folks with the most common CF mutation.

Targeting Cystic Fibrosis: Are Two Drugs Better than One?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Doctor with a child with cystic fibrosis who is taking part in clinical research studies. Credit: Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute

To explain the many challenges involved in turning scientific discoveries into treatments and cures, I often say, “Research is not a 100-yard dash, it’s a marathon.” Perhaps there is no better example of this than cystic fibrosis (CF). Back in 1989, I co-led the team that identified the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene—the gene responsible for this life-shortening, inherited disease that affects some 70,000 people worldwide [1]. Yet, it has taken more than 25 years of additional basic, translational, and clinical research to reach the point where we are today: seeing the emergence of precise combination drug therapy that may help about half of all people with CF.

CF is a recessive disease—that is, affected individuals have a misspelling of both copies of CFTR, one inherited from each parent; the parents are asymptomatic carriers. The first major advance in designer drug treatment for CF came in 2012, when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ivacaftor (Kalydeco™), the first drug to target specifically CF’s underlying molecular cause [2]. Exciting news, but the rub was that ivacaftor was expected to help only about 4 percent of CF patients—those who carry a copy of the relatively rare G551D mutation (that means a normal glycine at position 551 in the 1480 amino acid protein has been changed to aspartic acid) in CFTR. What could be done for the roughly 50 percent of CF patients who carry two copies of the far more common F508del mutation (that means a phenylalanine at position 508 is missing)? New findings show one answer may be to team ivacaftor with an experimental drug called lumacaftor.