Moderna vaccine

Study Shows Benefits of COVID-19 Vaccines and Boosters

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

As colder temperatures settle in and people spend more time gathered indoors, cases of COVID-19 and other respiratory illnesses almost certainly will rise. That’s why, along with scheduling your annual flu shot, it’s now recommended that those age 5 and up should get an updated COVID-19 booster shot [1,2]. Not only will these new boosters guard against the original strain of the coronavirus that started the pandemic, they will heighten your immunity to the Omicron variant and several of the subvariants that continue to circulate in the U.S. with devastating effects.

At last count, about 14.8 million people in the U.S.—including me—have rolled up their sleeves to receive an updated booster shot [3]. It’s a good start, but it also means that most Americans aren’t fully up to date on their COVID-19 vaccines. If you or your loved ones are among them, a new study may provide some needed encouragement to make an appointment at a nearby pharmacy or clinic to get boosted [4].

A team of NIH-supported researchers found a remarkably low incidence of severe COVID-19 illness last fall, winter, and spring among more than 1.6 million veterans who’d been vaccinated and boosted. Severe illness was also quite low in individuals without immune-compromising conditions.

These latest findings, published in the journal JAMA, come from a research group led by Dan Kelly, University of California, San Francisco. He and his team conducted their study drawing on existing health data from the Veterans Health Administration (VA) within a time window of July 2021 and May 2022.

They identified 1.6 million people who’d had a primary-care visit within the last two years and were fully vaccinated for COVID-19, which included receiving a booster shot. Almost three-quarters of those identified were 65 and older. Nearly all were male, and more than 70 percent had another pre-existing health condition that put them at greater risk of becoming seriously ill from a COVID-19 infection.

Over a 24-week follow-up period for each fully vaccinated individual, 125 per 10,000 people had a breakthrough infection. That’s about 1 percent. Just 8.9 in 10,000 fully vaccinated people—less than 0.1 percent—died or were hospitalized from COVID-19 pneumonia. Drilling down deeper into the data:

• Individuals with an immune-compromising condition had a very low rate of hospitalization or death. In this group, 39.6 per 10,000 people had a serious breakthrough infection. That translates to 0.3 percent.

• For people with other preexisting health conditions, including diabetes and heart disease, hospitalization or death totaled 0.07 percent, or 6.7 per 10,000 people.

• For otherwise healthy adults aged 65 and older, the incidence of hospitalization or death was 1.9 per 10,000 people, or 0.02 percent.

• For boosted participants 65 or younger with no high-risk conditions, hospitalization or death came to less than 1 per 10,000 people. That comes to less than 0.01 percent.

It’s worth noting that these results reflect a period when the Delta and Omicron variants were circulating, and available boosters still were based solely on the original variant. Heading into this winter, the hope is that the updated “bivalent” boosters from Pfizer and Moderna will offer even broader protection as this terrible virus continues to evolve.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention continues to recommend that everyone stay up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines. That means all adults and kids 5 and older are encouraged to get boosted if it has been at least two months since their last COVID-19 vaccine dose. For older people and those with other health conditions, it’s even more important given their elevated risk for severe illness.

What if you’ve had a COVID-19 infection recently? Getting vaccinated or boosted a few months after you’ve had a COVID-19 infection will offer you even better protection in the future.

So, if you are among the millions of Americans who’ve been vaccinated for COVID-19 but are now due for a booster, don’t delay. Get yourself boosted to protect your own health and the health of your loved ones as the holidays approach.

References:

[1] CDC recommends the first updated COVID-19 booster. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 1, 2022.

[2] CDC expands updated COVID-19 vaccines to include children ages 5 through 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 12, 2022.

[3] COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[4] Incidence of severe COVID-19 illness following vaccination and booster with BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines. Kelly JD, Leonard S, Hoggatt KJ, Boscardin WJ, Lum EN, Moss-Vazquez TA, Andino R, Wong JK, Byers A, Bravata DM, Tien PC, Keyhani S. JAMA. 2022 Oct 11;328(14):1427-1437.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Dan Kelly (University of California, San Francisco)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

How COVID-19 Immunity Holds Up Over Time

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

More than 215 million people in the United States are now fully vaccinated against the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for COVID-19 [1]. More than 40 percent—more than 94 million people—also have rolled up their sleeves for an additional, booster dose. Now, an NIH-funded study exploring how mRNA vaccines are performing over time comes as a reminder of just how important it will be to keep those COVID-19 vaccines up to date as coronavirus variants continue to circulate.

The results, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, show that people who received two doses of either the Pfizer or Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccines did generate needed virus-neutralizing antibodies [2]. But levels of those antibodies dropped considerably after six months, suggesting declining immunity over time.

The data also reveal that study participants had much reduced protection against newer SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Delta and Omicron. While antibody protection remained stronger in people who’d also had a breakthrough infection, even that didn’t appear to offer much protection against infection by the Omicron variant.

The new study comes from a team led by Shan-Lu Liu at The Ohio State University, Columbus. They wanted to explore how well vaccine-acquired immune protection holds up over time, especially in light of newly arising SARS-CoV-2 variants.

This is an important issue going forward because mRNA vaccines train the immune system to produce antibodies against the spike proteins that crown the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. These new variants often have mutated, or slightly changed, spike proteins compared to the original one the immune system has been trained to detect, potentially dampening the immune response.

In the study, the team collected serum samples from 48 fully vaccinated health care workers at four key time points: 1) before vaccination, 2) three weeks after the first dose, 3) one month after the second dose, and 4) six months after the second dose.

They then tested the ability of antibodies in those samples to neutralize spike proteins as a correlate for how well a vaccine works to prevent infection. The spike proteins represented five major SARS-CoV-2 variants. The variants included D614G, which arose very soon after the coronavirus first was identified in Wuhan and quickly took over, as well as Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Delta (B.1.617.2), and Omicron (B.1.1.529).

The researchers explored in the lab how neutralizing antibodies within those serum samples reacted to SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses representing each of the five variants. SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses are harmless viruses engineered, in this case, to bear coronavirus spike proteins on their surfaces. Because they don’t replicate, they are safe to study without specially designed biosafety facilities.

At any of the four time points, antibodies showed a minimal ability to neutralize the Omicron spike protein, which harbors about 30 mutations. These findings are consistent with an earlier study showing a significant decline in neutralizing antibodies against Omicron in people who’ve received the initial series of two shots, with improved neutralizing ability following an additional booster dose.

The neutralizing ability of antibodies against all other spike variants showed a dramatic decline from 1 to 6 months after the second dose. While there was a marked decline over time after both vaccines, samples from health care workers who’d received the Moderna vaccine showed about twice the neutralizing ability of those who’d received the Pfizer vaccine. The data also suggests greater immune protection in fully vaccinated healthcare workers who’d had a breakthrough infection with SARS-CoV-2.

In addition to recommending full vaccination for all eligible individuals, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends everyone 12 years and up should get a booster dose of either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines at least five months after completing the primary series of two shots [3]. Those who’ve received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine should get a booster at least two months after receiving the initial dose.

While plenty of questions about the durability of COVID-19 immunity over time remain, it’s clear that the rapid deployment of multiple vaccines over the course of this pandemic already has saved many lives and kept many more people out of the hospital. As the Omicron threat subsides and we start to look forward to better days ahead, it will remain critical for researchers and policymakers to continually evaluate and revise vaccination strategies and recommendations, to keep our defenses up as this virus continues to evolve.

References:

[1] COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 27, 2022.

[2] Neutralizing antibody responses elicited by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination wane over time and are boosted by breakthrough infection. Evans JP, Zeng C, Carlin C, Lozanski G, Saif LJ, Oltz EM, Gumina RJ, Liu SL. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Feb 15:eabn8057.

[3] COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Feb 2, 2022.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Shan-Lu Liu (The Ohio State University, Columbus)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Accelerating COVID-19 Vaccine Testing with ‘Correlates of Protection’

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

With Omicron now on so many people’s minds, public health officials and virologists around the world are laser focused on tracking the spread of this concerning SARS-CoV-2 variant and using every possible means to determine the effectiveness of our COVID-19 vaccines against it. Ultimately, the answer will depend on what happens in the real world. But it will also help to have a ready laboratory means for gauging how well a vaccine works, without having to wait many months for the results in the field.

With this latter idea in mind, I’m happy to share results of an NIH-funded effort to understand the immune responses associated with vaccine-acquired protection against SARS-CoV-2 [1]. The findings, based on the analysis of blood samples from more than 1,000 people who received the Moderna mRNA vaccine, show that antibody levels do correlate, albeit somewhat imperfectly, with how well a vaccine works to prevent infection.

Such measures of immunity, known as “correlates of protection,” have potential to support the approval of new or updated vaccines more rapidly. They’re also useful to show how well a vaccine will work in groups that weren’t represented in a vaccine’s initial testing, such as children, pregnant women, and those with certain health conditions.

The latest study, published in the journal Science, comes from a team of researchers led by Peter Gilbert, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle; David Montefiori, Duke University, Durham, NC; and Adrian McDermott, NIH’s Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The team started with existing data from the Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE) trial. This phase 3 study, conducted in 30,000 U.S. adults, found the Moderna vaccine was safe and about 94 percent effective in protecting people from symptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2 [2].

The researchers wanted to understand the underlying immune responses that afforded that impressive level of COVID-19 protection. They also sought to develop a means to measure those responses in the lab and quickly show how well a vaccine works.

To learn more, Gilbert’s team conducted tests on blood samples from COVE participants at the time of their second vaccine dose and again four weeks later. Two of the tests measured concentrations of binding antibodies (bAbs) that latch onto spike proteins that adorn the coronavirus surface. Two others measured the concentration of more broadly protective neutralizing antibodies (nAbs), which block SARS-CoV-2 from infecting human cells via ACE2 receptors found on their surfaces.

Each of the four tests showed antibody levels that were consistently higher in vaccine recipients who did not develop COVID-19 than in those who did. That is consistent with expectations. But these data also allowed the researchers to identify the specific antibody levels associated with various levels of protection from disease.

For those with the highest antibody levels, the vaccine offered an estimated 98 percent protection. Those with levels about 1,000 times lower still were well protected, but their vaccine efficacy was reduced to about 78 percent.

Based on any of the antibodies tested, the estimated COVID-19 risk was about 10 times lower for vaccine recipients with antibodies in the top 10 percent of values compared to those with antibodies that weren’t detectable. Overall, the findings suggest that tests for antibody levels can be applied to make predictions about an mRNA vaccine’s efficacy and may be used to guide modifications to the current vaccine regimen.

To understand the significance of this finding, consider that for a two-dose vaccine like Moderna or Pfizer, a trial using such correlates of protection might generate sufficient data in as little as two months [3]. As a result, such a trial might show whether a vaccine was meeting its benchmarks in 3 to 5 months. By comparison, even a rapid clinical trial done the standard way would take at least seven months to complete. Importantly also, trials relying on such correlates of protection require many fewer participants.

Since all four tests performed equally well, the researchers say it’s conceivable that a single antibody assay might be sufficient to predict how effective a vaccine will be in a clinical trial. Of course, such trials would require subsequent real-world studies to verify that the predicted vaccine efficacy matches actual immune protection.

It should be noted that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would need to approve the use of such correlates of protection before their adoption in any vaccine trial. But, to date, the totality of evidence on neutralizing antibody responses as correlates of protection—for which this COVE trial data is a major contributor—is impressive.

Neutralizing antibody levels are also now being considered for use in future coronavirus vaccine trials. Indeed, for the EUA of Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine for 5-to-11-year-olds, the FDA accepted pre-specified success criteria based on neutralizing antibody responses in this age group being as good as those observed in 16- to 25-year-olds [4].

Antibody levels also have been taken into consideration for decisions about booster shots. However, it’s important to note that antibody levels are not precise enough to help in deciding whether or not any particular individual needs a COVID-19 booster. Those recommendations are based on how much time has passed since the original immunization.

Getting a booster is a really good idea heading into the holidays. The Delta variant remains very much the dominant strain in the U.S., and we need to slow its spread. Most experts think the vaccines and boosters will also provide some protection against the Omicron variant—though the evidence we need is still a week or two away. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a COVID-19 booster for everyone ages 18 and up at least six months after your second dose of mRNA vaccine or two months after receiving the single dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine [5]. You may choose to get the same vaccine or a different one. And, there is a place near you that is offering the shot.

References:

[1] Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial.

Gilbert PB, Montefiori DC, McDermott AB, Fong Y, Benkeser D, Deng W, Zhou H, Houchens CR, Martins K, Jayashankar L, Castellino F, Flach B, Lin BC, O’Connell S, McDanal C, Eaton A, Sarzotti-Kelsoe M, Lu Y, Yu C, Borate B, van der Laan LWP, Hejazi NS, Huynh C, Miller J, El Sahly HM, Baden LR, Baron M, De La Cruz L, Gay C, Kalams S, Kelley CF, Andrasik MP, Kublin JG, Corey L, Neuzil KM, Carpp LN, Pajon R, Follmann D, Donis RO, Koup RA; Immune Assays Team§; Moderna, Inc. Team§; Coronavirus Vaccine Prevention Network (CoVPN)/Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE) Team§; United States Government (USG)/CoVPN Biostatistics Team§. Science. 2021 Nov 23:eab3435.

[2] Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, McGettigan J, Khetan S, Segall N, Solis J, Brosz A, Fierro C, Schwartz H, Neuzil K, Corey L, Gilbert P, Janes H, Follmann D, Marovich M, Mascola J, Polakowski L, Ledgerwood J, Graham BS, Bennett H, Pajon R, Knightly C, Leav B, Deng W, Zhou H, Han S, Ivarsson M, Miller J, Zaks T; COVE Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 4;384(5):403-416.

[3] A government-led effort to identify correlates of protection for COVID-19 vaccines. Koup RA, Donis RO, Gilbert PB, Li AW, Shah NA, Houchens CR. Nat Med. 2021 Sep;27(9):1493-1494.

[4] Evaluation of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in children 5 to 11 years of age. Walter EB, Talaat KR, Sabharwal C, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Paulsen GC, Barnett ED, Muñoz FM, Maldonado Y, Pahud BA, Domachowske JB, Simões EAF, Sarwar UN, Kitchin N, Cunliffe L, Rojo P, Kuchar E, Rämet M, Munjal I, Perez JL, Frenck RW Jr, Lagkadinou E, Swanson KA, Ma H, Xu X, Koury K, Mather S, Belanger TJ, Cooper D, Türeci Ö, Dormitzer PR, Şahin U, Jansen KU, Gruber WC; C4591007 Clinical Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2021 Nov 9:NEJMoa2116298.

[5] COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nov 29, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Combat COVID (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services)

Peter Gilbert (Fred Hutchison Cancer Research Center)

David Montefiori (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Adrian McDermott (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Breakthrough Infections in Vaccinated People Less Likely to Cause ‘Long COVID’

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s no question that vaccines are making a tremendous difference in protecting individuals and whole communities against infection and severe illness from SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. And now, there’s yet another reason to get the vaccine: in the event of a breakthrough infection, people who are fully vaccinated also are substantially less likely to develop Long COVID Syndrome, which causes brain fog, muscle pain, fatigue, and a constellation of other debilitating symptoms that can last for months after recovery from an initial infection.

These important findings published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases are the latest from the COVID Symptom Study [1]. This study allows everyday citizens in the United Kingdom to download a smartphone app and self-report data on their infection, symptoms, and vaccination status over a long period of time.

Previously, the study found that 1 in 20 people in the U.K. who got COVID-19 battled Long COVID symptoms for eight weeks or more. But this work was done before vaccines were widely available. What about the risk among those who got COVID-19 for the first time as a breakthrough infection after receiving a double dose of any of the three COVID-19 vaccines (Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca) authorized for use in the U.K.?

To answer that question, Claire Steves, King’s College, London, and colleagues looked to frequent users of the COVID Symptom Study app on their smartphones. In its new work, Steves’ team was interested in analyzing data submitted by folks who’d logged their symptoms, test results, and vaccination status between December 9, 2020, and July 4, 2021. The team found there were more than 1.2 million adults who’d received a first dose of vaccine and nearly 1 million who were fully vaccinated during this period.

The data show that only 0.2 percent of those who were fully vaccinated later tested positive for COVID-19. While accounting for differences in age, sex, and other risk factors, the researchers found that fully vaccinated individuals who developed breakthrough infections were about half (49 percent) as likely as unvaccinated people to report symptoms of Long COVID Syndrome lasting at least four weeks after infection.

The most common symptoms were similar in vaccinated and unvaccinated adults with COVID-19, and included loss of smell, cough, fever, headaches, and fatigue. However, all of these symptoms were milder and less frequently reported among the vaccinated as compared to the unvaccinated.

Vaccinated people who became infected were also more likely than the unvaccinated to be asymptomatic. And, if they did develop symptoms, they were half as likely to report multiple symptoms in the first week of illness. Another vaccination benefit was that people with a breakthrough infection were about a third as likely to report any severe symptoms. They also were more than 70 percent less likely to require hospitalization.

We still have a lot to learn about Long COVID, and, to get the answers, NIH has launched the RECOVER Initiative. The initiative will study tens of thousands of COVID-19 survivors to understand why many individuals don’t recover as quickly as expected, and what might be the cause, prevention, and treatment for Long COVID.

In the meantime, these latest findings offer the encouraging news that help is already here in the form of vaccines, which provide a very effective way to protect against COVID-19 and greatly reduce the odds of Long COVID if you do get sick. So, if you haven’t done so already, make a plan to protect your own health and help end this pandemic by getting yourself fully vaccinated. Vaccines are free and available near to you—just go to vaccines.gov or text your zip code to 438829.

Reference:

[1] Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Merino J, Sudre CH, Molteni E, Berry S, Canas LS, Graham MS, Klaser K, Modat M, Murray B, Kerfoot E, Chen L, Deng J, Österdahl MF, Cheetham NJ, Drew DA, Nguyen LH, Pujol JC, Hu C, Selvachandran S, Polidori L, May A, Wolf J, Chan AT, Hammers A, Duncan EL, Spector TD, Ourselin S, Steves CJ. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 1:S1473-3099(21)00460-6.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Claire Steves (King’s College London, United Kingdom)

mRNA Vaccines May Pack More Persistent Punch Against COVID-19 Than Thought

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Many people, including me, have experienced a sense of gratitude and relief after receiving the new COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. But all of us are also wondering how long the vaccines will remain protective against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19.

Earlier this year, clinical trials of the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines indicated that both immunizations appeared to protect for at least six months. Now, a study in the journal Nature provides some hopeful news that these mRNA vaccines may be protective even longer [1].

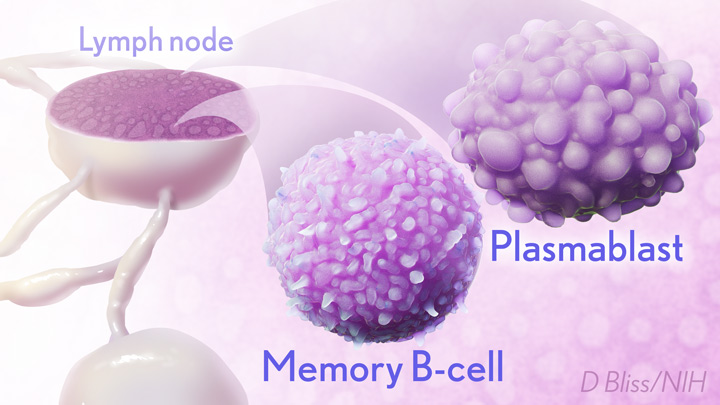

In the new study, researchers monitored key immune cells in the lymph nodes of a group of people who received both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine. The work consistently found hallmarks of a strong, persistent immune response against SARS-CoV-2 that could be protective for years to come.

Though more research is needed, the findings add evidence that people who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may not need an additional “booster” shot for quite some time, unless SARS-CoV-2 evolves into new forms, or variants, that can evade this vaccine-induced immunity. That’s why it remains so critical that more Americans get vaccinated not only to protect themselves and their loved ones, but to help stop the virus’s spread in their communities and thereby reduce its ability to mutate.

The new study was conducted by an NIH-supported research team led by Jackson Turner, Jane O’Halloran, Rachel Presti, and Ali Ellebedy at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. That work builds upon the group’s previous findings that people who survived COVID-19 had immune cells residing in their bone marrow for at least eight months after the infection that could recognize SARS-CoV-2 [2]. The researchers wanted to see if similar, persistent immunity existed in people who hadn’t come down with COVID-19 but who were immunized with an mRNA vaccine.

To find out, Ellebedy and team recruited 14 healthy adults who were scheduled to receive both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Three weeks after their first dose of vaccine, the volunteers underwent a lymph node biopsy, primarily from nodes in the armpit. Similar biopsies were repeated at four, five, seven, and 15 weeks after the first vaccine dose.

The lymph nodes are where the human immune system establishes so-called germinal centers, which function as “training camps” that teach immature immune cells to recognize new disease threats and attack them with acquired efficiency. In this case, the “threat” is the spike protein of SARS-COV-2 encoded by the vaccine.

By the 15-week mark, all of the participants sampled continued to have active germinal centers in their lymph nodes. These centers produced an army of cells trained to remember the spike protein, along with other types of cells, including antibody-producing plasmablasts, that were locked and loaded to neutralize this key protein. In fact, Ellebedy noted that even after the study ended at 15 weeks, he and his team continued to find no signs of germinal center activity slowing down in the lymph nodes of the vaccinated volunteers.

Ellebedy said the immune response observed in his team’s study appears so robust and persistent that he thinks that it could last for years. The researcher based his assessment on the fact that germinal center reactions that persist for several months or longer usually indicate an extremely vigorous immune response that culminates in the production of large numbers of long-lasting immune cells, called memory B cells. Some memory B cells can survive for years or even decades, which gives them the capacity to respond multiple times to the same infectious agent.

This study raises some really important issues for which we still don’t have complete answers: What is the most reliable correlate of immunity from COVID-19 vaccines? Are circulating spike protein antibodies (the easiest to measure) the best indicator? Do we need to know what’s happening in the lymph nodes? What about the T cells that are responsible for cell-mediated immunity?

If you follow the news, you may have seen a bit of a dust-up in the last week on this topic. Pfizer announced the need for a booster shot has become more apparent, based on serum antibodies. Meanwhile, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said such a conclusion would be premature, since vaccine protection looks really good right now, including for the delta variant that has all of us concerned.

We’ve still got a lot more to learn about the immunity generated by the mRNA vaccines. But this study—one of the first in humans to provide direct evidence of germinal center activity after mRNA vaccination—is a good place to continue the discussion.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Turner JS, O’Halloran JA, Kalaidina E, Kim W, Schmitz AJ, Zhou JQ, Lei T, Thapa M, Chen RE, Case JB, Amanat F, Rauseo AM, Haile A, Xie X, Klebert MK, Suessen T, Middleton WD, Shi PY, Krammer F, Teefey SA, Diamond MS, Presti RM, Ellebedy AH. Nature. 2021 Jun 28. [Online ahead of print]

[2] SARS-CoV-2 infection induces long-lived bone marrow plasma cells in humans. Turner JS, Kim W, Kalaidina E, Goss CW, Rauseo AM, Schmitz AJ, Hansen L, Haile A, Klebert MK, Pusic I, O’Halloran JA, Presti RM, Ellebedy AH. Nature. 2021 May 24. [Online ahead of print]

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Ellebedy Lab (Washington University, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

How Immunity Generated from COVID-19 Vaccines Differs from an Infection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A key issue as we move closer to ending the pandemic is determining more precisely how long people exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, will make neutralizing antibodies against this dangerous coronavirus. Finding the answer is also potentially complicated with new SARS-CoV-2 “variants of concern” appearing around the world that could find ways to evade acquired immunity, increasing the chances of new outbreaks.

Now, a new NIH-supported study shows that the answer to this question will vary based on how an individual’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were generated: over the course of a naturally acquired infection or from a COVID-19 vaccine. The new evidence shows that protective antibodies generated in response to an mRNA vaccine will target a broader range of SARS-CoV-2 variants carrying “single letter” changes in a key portion of their spike protein compared to antibodies acquired from an infection.

These results add to evidence that people with acquired immunity may have differing levels of protection to emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. More importantly, the data provide further documentation that those who’ve had and recovered from a COVID-19 infection still stand to benefit from getting vaccinated.

These latest findings come from Jesse Bloom, Allison Greaney, and their team at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. In an earlier study, this same team focused on the receptor binding domain (RBD), a key region of the spike protein that studs SARS-CoV-2’s outer surface. This RBD is especially important because the virus uses this part of its spike protein to anchor to another protein called ACE2 on human cells before infecting them. That makes RBD a prime target for both naturally acquired antibodies and those generated by vaccines. Using a method called deep mutational scanning, the Seattle group’s previous study mapped out all possible mutations in the RBD that would change the ability of the virus to bind ACE2 and/or for RBD-directed antibodies to strike their targets.

In their new study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Bloom, Greaney, and colleagues looked again to the thousands of possible RBD variants to understand how antibodies might be expected to hit their targets there [1]. This time, they wanted to explore any differences between RBD-directed antibodies based on how they were acquired.

Again, they turned to deep mutational scanning. First, they created libraries of all 3,800 possible RBD single amino acid mutants and exposed the libraries to samples taken from vaccinated individuals and unvaccinated individuals who’d been previously infected. All vaccinated individuals had received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine. This vaccine works by prompting a person’s cells to produce the spike protein, thereby launching an immune response and the production of antibodies.

By closely examining the results, the researchers uncovered important differences between acquired immunity in people who’d been vaccinated and unvaccinated people who’d been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, antibodies elicited by the mRNA vaccine were more focused to the RBD compared to antibodies elicited by an infection, which more often targeted other portions of the spike protein. Importantly, the vaccine-elicited antibodies targeted a broader range of places on the RBD than those elicited by natural infection.

These findings suggest that natural immunity and vaccine-generated immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will differ in how they recognize new viral variants. What’s more, antibodies acquired with the help of a vaccine may be more likely to target new SARS-CoV-2 variants potently, even when the variants carry new mutations in the RBD.

It’s not entirely clear why these differences in vaccine- and infection-elicited antibody responses exist. In both cases, RBD-directed antibodies are acquired from the immune system’s recognition and response to viral spike proteins. The Seattle team suggests these differences may arise because the vaccine presents the viral protein in slightly different conformations.

Also, it’s possible that mRNA delivery may change the way antigens are presented to the immune system, leading to differences in the antibodies that get produced. A third difference is that natural infection only exposes the body to the virus in the respiratory tract (unless the illness is very severe), while the vaccine is delivered to muscle, where the immune system may have an even better chance of seeing it and responding vigorously.

Whatever the underlying reasons turn out to be, it’s important to consider that humans are routinely infected and re-infected with other common coronaviruses, which are responsible for the common cold. It’s not at all unusual to catch a cold from seasonal coronaviruses year after year. That’s at least in part because those viruses tend to evolve to escape acquired immunity, much as SARS-CoV-2 is now in the process of doing.

The good news so far is that, unlike the situation for the common cold, we have now developed multiple COVID-19 vaccines. The evidence continues to suggest that acquired immunity from vaccines still offers substantial protection against the new variants now circulating around the globe.

The hope is that acquired immunity from the vaccines will indeed produce long-lasting protection against SARS-CoV-2 and bring an end to the pandemic. These new findings point encouragingly in that direction. They also serve as an important reminder to roll up your sleeve for the vaccine if you haven’t already done so, whether or not you’ve had COVID-19. Our best hope of winning this contest with the virus is to get as many people immunized now as possible. That will save lives, and reduce the likelihood of even more variants appearing that might evade protection from the current vaccines.

Reference:

[1] Antibodies elicited by mRNA-1273 vaccination bind more broadly to the receptor binding domain than do those from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Gentles LE, Crawford KHD, Starr TN, Malone KD, Chu HY, Bloom JD. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Jun 8.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Bloom Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Studies Confirm COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines Safe, Effective for Pregnant Women

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Clinical trials have shown that COVID-19 vaccines are remarkably effective in protecting those age 12 and up against infection by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The expectation was that they would work just as well to protect pregnant women. But because pregnant women were excluded from the initial clinical trials, hard data on their safety and efficacy in this important group has been limited.

So, I’m pleased to report results from two new studies showing that the two COVID-19 mRNA vaccines now available in the United States appear to be completely safe for pregnant women. The women had good responses to the vaccines, producing needed levels of neutralizing antibodies and immune cells known as memory T cells, which may offer more lasting protection. The research also indicates that the vaccines might offer protection to infants born to vaccinated mothers.

In one study, published in JAMA [1], an NIH-supported team led by Dan Barouch, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, wanted to learn whether vaccines would protect mother and baby. To find out, they enrolled 103 women, aged 18 to 45, who chose to get either the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccines from December 2020 through March 2021.

The sample included 30 pregnant women,16 women who were breastfeeding, and 57 women who were neither pregnant nor breastfeeding. Pregnant women in the study got their first dose of vaccine during any trimester, although most got their shots in the second or third trimester. Overall, the vaccine was well tolerated, although some women in each group developed a transient fever after the second vaccine dose, a common side effect in all groups that have been studied.

After vaccination, women in all groups produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, those antibodies neutralized SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. The researchers also found those antibodies in infant cord blood and breast milk, suggesting that they were passed on to afford some protection to infants early in life.

The other NIH-supported study, published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology, was conducted by a team led by Jeffery Goldstein, Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago [2]. To explore any possible safety concerns for pregnant women, the team took a first look for any negative effects of vaccination on the placenta, the vital organ that sustains the fetus during gestation.

The researchers detected no signs that the vaccines led to any unexpected damage to the placenta in this study, which included 84 women who received COVID-19 mRNA vaccines during pregnancy, most in the third trimester. As in the other study, the team found that vaccinated pregnant women showed a robust response to the vaccine, producing needed levels of neutralizing antibodies.

Overall, both studies show that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are safe and effective in pregnancy, with the potential to benefit both mother and baby. Pregnant women also are more likely than women who aren’t pregnant to become severely ill should they become infected with this devastating coronavirus [3]. While pregnant women are urged to consult with their obstetrician about vaccination, growing evidence suggests that the best way for women during pregnancy or while breastfeeding to protect themselves and their families against COVID-19 is to roll up their sleeves and get either one of the mRNA vaccines now authorized for emergency use.

References:

[1] Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in pregnant and lactating women. Collier AY, McMahan K, Yu J, Tostanoski LH, Aguayo R, Ansel J, Chandrashekar A, Patel S, Apraku Bondzie E, Sellers D, Barrett J, Sanborn O, Wan H, Chang A, Anioke T, Nkolola J, Bradshaw C, Jacob-Dolan C, Feldman J, Gebre M, Borducchi EN, Liu J, Schmidt AG, Suscovich T, Linde C, Alter G, Hacker MR, Barouch DH. JAMA. 2021 May 13.

[2] Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccination in pregnancy: Measures of immunity and placental histopathology. Shanes ED, Otero S, Mithal LB, Mupanomunda CA, Miller ES, Goldstein JA. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 May 11.

[3] COVID-19 vaccines while pregnant or breastfeeding. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Barouch Laboratory (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Jeffery Goldstein (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering