mouth

Connecting the Dots: Oral Infection to Rheumatoid Arthritis

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

To keep your teeth and gums healthy for a lifetime, it’s important to brush and floss each day and see your dentist regularly. But what you might not often stop to consider is how essential good oral health really is to your overall well-being. The mouth, after all, is connected to the rest of the body, and oral infections can contribute to problems elsewhere.

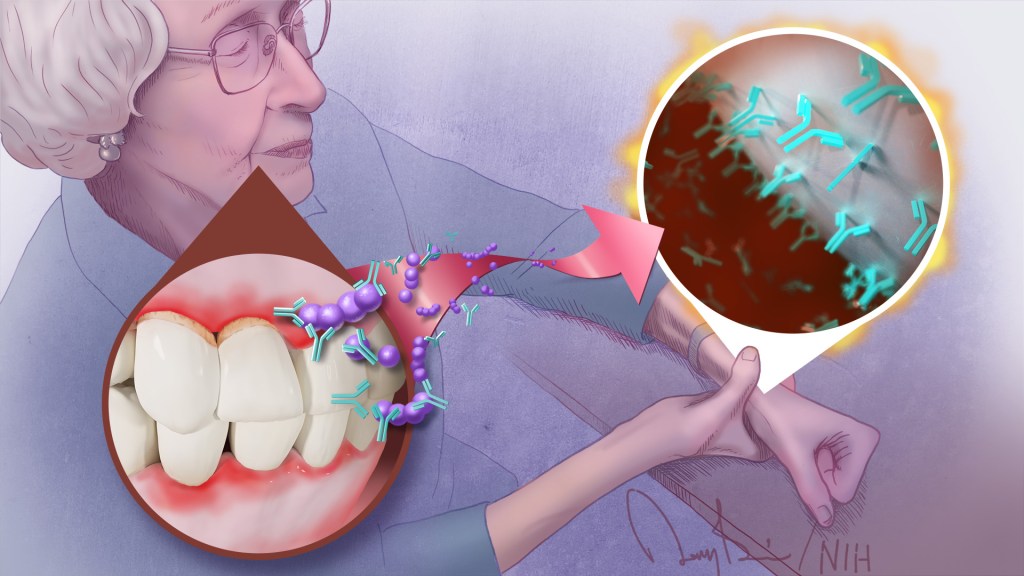

A good case in point comes from a study just published in the journal Science Translational Medicine. The study, though small, offers some of the most convincing evidence yet for a direct link between gum, or periodontal, disease and the rheumatoid arthritis that flares most commonly in the hands, wrists, and knees [1]. If confirmed in larger follow-up studies, the finding suggests that one way for people with both diseases to contend with painful arthritic flare-ups will be to prevent them by practicing good oral hygiene and controlling their periodontal disease.

For many years, there had been suggestions that the oral bacteria causing periodontal disease might contribute to rheumatoid arthritis. For instance, past studies have found that periodontal disease occurs even more often in people with rheumatoid arthritis. People with both conditions also tend to have more severe arthritic symptoms that can be more stubbornly resistant to treatment.

What’s been missing is the precise underlying mechanisms to confirm the connection. To help connect the dots, a research team, which included Dana Orange, Rockefeller University, New York, NY, and William Robinson, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, decided to look closer.

They looked first in the blood, not directly at an arthritic joint or an inflamed periodontium, the tissues that hold a tooth in place. They were interested in whether telltale changes in the blood of people with rheumatoid arthritis correlated with the start of another painful flare-up in one or more of their joints.

One of those possible changes involves proteins that carry a particular chemical modification that places the amino acid citrulline on their surface. These citrulline-marked proteins are found in many parts of the human body, including the joints. Intriguingly, they also are present on bacteria, including those in the mouth.

Because of this bacterial connection, the researchers looked in the blood for a specific set of antibodies known as ACPAs, short for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies. They recognize citrullinated proteins that are foreign to the body and mark them for attack.

But the attack isn’t always perfectly aimed, and studies have shown the presence of ACPAs in the joints of people with rheumatoid arthritis is associated with increasing disease activity and more frequent arthritis flares. Periodontal disease, too, is especially common in people with rheumatoid arthritis who have abnormally high levels of circulating ACPAs.

In the new study, the researchers followed five women with rheumatoid arthritis for one to four years. Two of them had severe periodontal disease while the other three had no periodontal disease.

Each week, the study volunteers provided a small blood sample for researchers to study changes at the level of RNA, the genetic material that encodes proteins. They also studied changes in certain immune cells, along with any changes in their medication, dental care, or arthritis symptoms. For additional information, they also looked at blood and joint fluid samples from 67 other people with and without arthritis, including individuals with healthy gums or mild, moderate, or severe periodontal disease.

Overall, the evidence shows that people with more severe periodontal disease experienced repeated influxes of oral bacteria into their blood even when they hadn’t had a recent dental procedure. These findings suggested that when their inflamed gums became more damaged and “leaky,” bacteria in the mouth could spill into the bloodstream.

The researchers also found that those oral invaders carried many citrullinated proteins. Once they got into the bloodstream, inflammatory immune cells detected them and released ACPAs.

The researchers showed in the lab that those antibodies bind the same oral bacteria detected in the blood of people with periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis. In fact, those with both conditions had a wide variety of genetically distinct ACPAs, as would be expected if their immune systems were challenged repeatedly over time with oral bacteria.

The overarching idea is that these antibodies prime the immune system to attack oral bacteria. But after it gets started, the attack mistakenly expands and targets citrullinated proteins in the joints. That triggers a flare-up in a joint and the characteristic inflammation, stiffness, and joint damage.

While more study is needed to fill in the molecular details, this discovery raises an encouraging possibility. Taking care of your teeth and periodontal disease isn’t just a wise idea to maintain good oral health over a lifetime. For some of the approximately 1 million Americans with rheumatoid arthritis, it may help to manage and perhaps even prevent a painful flare-up in one or more of their affected joints.

Reference:

[1] Oral mucosal breaks trigger anti-citrullinated bacterial and human protein antibody responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Brewer RC, Lanz TV, Hale CR, Sepich-Poore GD, Martino C, Swafford AD, Carroll TS, Kongpachith S, Blum LK, Elliott SE, Blachere NE, Parveen S, Fak J, Yao V, Troyanskaya O, Frank MO, Bloom MS, Jahanbani S, Gomez AM, Iyer R, Ramadoss NS, Sharpe O, Chandrasekaran S, Kelmenson LB, Wang Q, Wong H, Torres HL, Wiesen M, Graves DT, Deane KD, Holers VM, Knight R, Darnell RB, Robinson WH, Orange DE. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Feb 22;15(684):eabq8476.

Links:

Rheumatoid Arthritis (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases)

Periodontal (Gum) Disease (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Oral Hygiene (NIDCR)

Dana Orange (Rockefeller University, New York NY)

Robinson Lab (Stanford University, Stanford, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Study Demonstrates Saliva Can Spread Novel Coronavirus

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

COVID-19 is primarily considered a respiratory illness that affects the lungs, upper airways, and nasal cavity. But COVID-19 can also affect other parts of the body, including the digestive system, blood vessels, and kidneys. Now, a new study has added something else: the mouth.

The study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, shows that SARS-CoV-2, which is the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, can actively infect cells that line the mouth and salivary glands. The new findings may help explain why COVID-19 can be detected by saliva tests, and why about half of COVID-19 cases include oral symptoms, such as loss of taste, dry mouth, and oral ulcers. These results also suggest that the mouth and its saliva may play an important—and underappreciated—role in spreading SARS-CoV-2 throughout the body and, perhaps, transmitting it from person to person.

The latest work comes from Blake Warner of NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; Kevin Byrd, Adams School of Dentistry at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; and their international colleagues. The researchers were curious about whether the mouth played a role in transmitting SARS-CoV-2. They were already aware that transmission is more likely when people speak, cough, and even sing. They also knew from diagnostic testing that the saliva of people with COVID-19 can contain high levels of SARS-CoV-2. But did that virus in the mouth and saliva come from elsewhere? Or, was SARS-CoV-2 infecting and replicating in cells within the mouth as well?

To find out, the research team surveyed oral tissue from healthy people in search of cells that express the ACE2 receptor protein and the TMPRSS2 enzyme protein, both of which SARS-CoV-2 depends upon to enter and infect human cells. They found the proteins may be expressed individually in the primary cells of all types of salivary glands and in tissues lining the oral cavity. Indeed, a small portion of salivary gland and gingival (gum) cells around our teeth, simultaneously expressed the genes encoding ACE2 and TMPRSS2.

Next, the team detected signs of SARS-CoV-2 in just over half of the salivary gland tissue samples that it examined from people with COVID-19. The samples included salivary gland tissue from one person who had died from COVID-19 and another with acute illness.

The researchers also found evidence that the coronavirus was actively replicating to make more copies of itself. In people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19, oral cells that shed into the saliva bathing the mouth were found to contain RNA for SARS-CoV-2, as well its proteins that it uses to enter human cells.

The researchers then collected saliva from another group of 35 volunteers, including 27 with mild COVID-19 symptoms and another eight who were asymptomatic. Of the 27 people with symptoms, those with virus in their saliva were more likely to report loss of taste and smell, suggesting that oral infection might contribute to those symptoms of COVID-19, though the primary cause may be infection of the olfactory tissues in the nose.

Another important question is whether SARS-CoV-2, while suspended in saliva, can infect other healthy cells. To get the answer, the researchers exposed saliva from eight people with asymptomatic COVID-19 to healthy cells grown in a lab dish. Saliva from two of the infected volunteers led to infection of the healthy cells. These findings raise the unfortunate possibility that even people with asymptomatic COVID-19 might unknowingly transmit SARS-CoV-2 to other people through their saliva.

Overall, the findings suggest that the mouth plays a greater role in COVID-19 infection and transmission than previously thought. The researchers suggest that virus-laden saliva, when swallowed or inhaled, may spread virus into the throat, lungs, or digestive system. Knowing this raises the hope that a better understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 infects the mouth could help in pointing to new ways to prevent the spread of this devastating virus.

Reference:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 infection of the oral cavity and saliva. Huang N, Pérez P, Kato T, Mikami Y, Chiorini JA, Kleiner DE, Pittaluga S, Hewitt SM, Burbelo PD, Chertow D; NIH COVID-19 Autopsy Consortium; HCA Oral and Craniofacial Biological Network, Frank K, Lee J, Boucher RC, Teichmann SA, Warner BM, Byrd KM, et. al Nat Med. 2021 Mar 25.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Saliva & Salivary Gland Disorders (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Blake Warner (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Kevin Byrd (Adams School of Dentistry at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

NIH Support: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences