mRNA vaccine

Persistence Pays Off: Recognizing Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, the 2023 Nobel Prize Winners in Physiology or Medicine

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Last week, biochemist Katalin Karikó and immunologist Drew Weissman earned the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries that enabled the development of effective messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines against COVID-19. On behalf of the NIH community, I’d like to congratulate Karikó and Weissman and thank them for their persistence in pursuing their investigations. NIH is proud to have supported their seminal research, cited by the Nobel Assembly as key publications.1,2,3

While the lifesaving benefits of mRNA vaccines are now clearly realized, Karikó and Weissman’s breakthrough finding in 2005 was not fully appreciated at the time as to why it would be significant. However, their dogged dedication to gaining a better understanding of how RNA interacts with the immune system underscores the often-underappreciated importance of incremental research. Following where the science leads through step-by-step investigations often doesn’t appear to be flashy, but it can end up leading to major advances.

To best describe Karikó and Weissman’s discovery, I’ll first do a quick review of vaccine history. As many of you know, vaccines stimulate our immune systems to protect us from getting infected or from getting very sick from a specific pathogen. Since the late 1700s, scientists have used various approaches to design effective vaccines. Some vaccines introduce a weakened or noninfectious version of a virus to the body, while others present only a small part of the virus, like a protein. The immune system detects the weak or partial virus and develops specialized defenses against it. These defenses work to protect us if we are ever exposed to the real virus.

In the early 1990s, scientists began exploring a different approach to vaccines that involved delivering genetic material, or instructions, so the body’s own cells could make the virus proteins that stimulate an immune response.4,5 Because this approach eliminates the step of growing virus or virus protein in the laboratory—which can be difficult to do in very large quantities and can require a lot of time and money—it had potential, in theory, to be a faster and cheaper way to manufacture vaccines.

Scientists were exploring two types of vaccines as part of this new approach: DNA vaccines and messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines. DNA vaccines deliver an encoded protein recipe that the cell first copies or transcribes before it starts making protein. For mRNA vaccines, the transcription process is done in the laboratory, and the vaccine delivers the “readable” instructions to the cell for making protein. However, mRNA was not immediately a practical vaccine approach due to several scientific hurdles, including that it caused inflammatory reactions that could be unhealthy for people.

Unfazed by the challenges, Karikó and Weissman spent years pursuing research on RNA and the immune system. They had a brilliant idea that they turned into a significant discovery in 2005 when they proved that inserting subtle chemical modifications to lab-transcribed mRNA eliminated the unwanted inflammatory response.1 In later studies, the pair showed that these chemical modifications also increased protein production.2,3 Both discoveries would be critical to advancing the use of mRNA-based vaccines and therapies.

Earlier theories that mRNA could enable rapid vaccine development turned out to be true. By March 2020, the first clinical trial of an mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 had begun enrolling volunteers, and by December 2020, health care workers were receiving their first shots. This unprecedented timeline was only possible because of Karikó and Weissman’s decades of work, combined with the tireless efforts of many academic, industry and government scientists, including several from the NIH intramural program. Now, researchers are exploring how mRNA could be used in vaccines for other infectious diseases and in cancer vaccines.

As an investigator myself, I’m fascinated by how science continues to build on itself—a process that is done out of the public eye. Luckily every year, the Nobel Prize briefly illuminates for the larger public this long arc of scientific discovery. The Nobel Assembly’s recognition of Karikó and Weissman is a tribute to all scientists who do the painstaking work of trying to understand how things work. Many of the tools we have today to better prevent and treat diseases would not have been possible without the brilliance, tenacity and grit of researchers like Karikó and Weissman.

References:

- K Karikó, et al. Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors: The impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008 (2005).

- K Karikó, et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Molecular Therapy DOI: 10.1038/mt.2008.200 (2008).

- BR Anderson, et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA enhances translation by diminishing PKR activation. Nucleic Acids Research DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkq347 (2010).

- DC Tang, et al. Genetic immunization is a simple method for eliciting an immune response. Nature DOI: 10.1038/356152a0 (1992).

- F Martinon, et al. Induction of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo by liposome-entrapped mRNA. European Journal of Immunology DOI: 10.1002/eji.1830230749 (1993).

NIH Support:

Katalin Karikó: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Drew Weissman: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Encouraging First-in-Human Results for a Promising HIV Vaccine

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

In recent years, we’ve witnessed some truly inspiring progress in vaccine development. That includes the mRNA vaccines that were so critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, the first approved vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and a “universal flu vaccine” candidate that could one day help to thwart future outbreaks of more novel influenza viruses.

Inspiring progress also continues to be made toward a safe and effective vaccine for HIV, which still infects about 1.5 million people around the world each year [1]. A prime example is the recent first-in-human trial of an HIV vaccine made in the lab from a unique protein nanoparticle, a molecular construct measuring just a few billionths of a meter.

The results of this early phase clinical study, published recently in the journal Science Translational Medicine [2] and earlier in Science [3], showed that the experimental HIV nanoparticle vaccine is safe in people. While this vaccine alone will not offer HIV protection and is intended to be part of an eventual broader, multistep vaccination regimen, the researchers also determined that it elicited a robust immune response in nearly all 36 healthy adult volunteers.

How robust? The results show that the nanoparticle vaccine, known by the lab name eOD-GT8 60-mer, successfully expanded production of a rare type of antibody-producing immune B cell in nearly all recipients.

What makes this rare type of B cell so critical is that it is the cellular precursor of other B cells capable of producing broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) to protect against diverse HIV variants. Also very good news, the vaccine elicited broad responses from helper T cells. They play a critical supportive role for those essential B cells and their development of the needed broadly neutralizing antibodies.

For decades, researchers have brought a wealth of ideas to bear on developing a safe and effective HIV vaccine. However, crossing the finish line—an FDA-approved vaccine—has proved profoundly difficult.

A major reason is the human immune system is ill equipped to recognize HIV and produce the needed infection-fighting antibodies. And yet the medical literature includes reports of people with HIV who have produced the needed antibodies, showing that our immune system can do it.

But these people remain relatively rare, and the needed robust immunity clocks in only after many years of infection. On top of that, HIV has a habit of mutating rapidly to produce a wide range of identity-altering variants. For a vaccine to work, it most likely will need to induce the production of bnAbs that recognize and defend against not one, but the many different faces of HIV.

To make the uncommon more common became the quest of a research team that includes scientists William Schief, Scripps Research and IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center, La Jolla, CA; M. Juliana McElrath, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle; and Kristen Cohen, a former member of the McElrath lab now at Moderna, Cambridge, MA. The team, with NIH collaborators and support, has been plotting out a stepwise approach to train the immune system into making the needed bnAbs that recognize many HIV variants.

The critical first step is to prime the immune system to make more of those coveted bnAb-precursor B cells. That’s where the protein nanoparticle known as eOD-GT8 60-mer enters the picture.

This nanoparticle, administered by injection, is designed to mimic a small, highly conserved segment of an HIV protein that allows the virus to bind and infect human cells. In the body, those nanoparticles launch an immune response and then quickly vanish. But because this important protein target for HIV vaccines is so tiny, its signal needed amplification for immune system detection.

To boost the signal, the researchers started with a bacterial protein called lumazine synthase (LumSyn). It forms the scaffold, or structural support, of the self-assembling nanoparticle. Then, they added to the LumSyn scaffold 60 copies of the key HIV protein. This louder HIV signal is tailored to draw out and engage those very specific B cells with the potential to produce bnAbs.

As the first-in-human study showed, the nanoparticle vaccine was safe when administered twice to each participant eight weeks apart. People reported only mild to moderate side effects that went away in a day or two. The vaccine also boosted production of the desired B cells in all but one vaccine recipient (35 of 36). The idea is that this increase in essential B cells sets the stage for the needed additional steps—booster shots that can further coax these cells along toward making HIV protective bnAbs.

The latest finding in Science Translational Medicine looked deeper into the response of helper T cells in the same trial volunteers. Again, the results appear very encouraging. The researchers observed CD4 T cells specific to the HIV protein and to the LumSyn in 84 percent and 93 percent of vaccine recipients. Their analyses also identified key hotspots that the T cells recognized, which is important information for refining future vaccines to elicit helper T cells.

The team reports that they’re now collaborating with Moderna, the developer of one of the two successful mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, on an mRNA version of eOD-GT8 60-mer. That’s exciting because mRNA vaccines are much faster and easier to produce and modify, which should now help to move this line of research along at a faster clip.

Indeed, two International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI)-sponsored clinical trials of the mRNA version are already underway, one in the U.S. and the other in Rwanda and South Africa [4]. It looks like this team and others are now on a promising track toward following the basic science and developing a multistep HIV vaccination regimen that guides the immune response and its stepwise phases in the right directions.

As we look back on more than 40 years of HIV research, it’s heartening to witness the progress that continues toward ending the HIV epidemic. This includes the recent FDA approval of the drug Apretude, the first injectable treatment option for pre-exposure prevention of HIV, and the continued global commitment to produce a safe and effective vaccine.

References:

[1] Global HIV & AIDS statistics fact sheet. UNAIDS.

[2] A first-in-human germline-targeting HIV nanoparticle vaccine induced broad and publicly targeted helper T cell responses. Cohen KW, De Rosa SC, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Fiore-Gartland A, Laufer DS, Koup RA, McDermott AB, Schief WR, McElrath MJ. Sci Transl Med. 2023 May 24;15(697):eadf3309.

[3] Vaccination induces HIV broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in humans. Leggat DJ, Cohen KW, Willis JR, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Koup RA, Laufer DS, McElrath MJ, McDermott AB, Schief WR. Science. 2022 Dec 2;378(6623):eadd6502.

[4] IAVI and Moderna launch first-in-Africa clinical trial of mRNA HIV vaccine development program. IAVI. May 18, 2022.

Links:

Progress Toward an Eventual HIV Vaccine, NIH Research Matters, Dec. 13, 2022.

NIH Statement on HIV Vaccine Awareness Day 2023, Auchincloss H, Kapogiannis, B. May, 18, 2023.

HIV Vaccine Development (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) (New York, NY)

William Schief (Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA)

Julie McElrath (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

McElrath Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Experimental mRNA Vaccine May Protect Against All 20 Influenza Virus Subtypes

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Flu season is now upon us, and protecting yourself and loved ones is still as easy as heading to the nearest pharmacy for your annual flu shot. These vaccines are formulated each year to protect against up to four circulating strains of influenza virus, and they generally do a good job of this. What they can’t do is prevent future outbreaks of more novel flu viruses that occasionally spill over from other species into humans, thereby avoiding a future influenza pandemic.

On this latter and more-challenging front, there’s some encouraging news that was published recently in the journal Science [1]. An NIH-funded team has developed a unique “universal flu vaccine” that, with one seasonal shot, that has the potential to build immune protection against any of the 20 known subtypes of influenza virus and protect against future outbreaks.

While this experimental flu vaccine hasn’t yet been tested in people, the concept has shown great promise in advanced pre-clinical studies. Human clinical trials will hopefully start in the coming year. The researchers don’t expect that this universal flu vaccine will prevent influenza infection altogether. But, like COVID-19 vaccines, the new flu vaccine should help to reduce severe influenza illnesses and deaths when a person does get sick.

So, how does one develop a 20-in-1“multivalent” flu vaccine? It turns out that the key is the same messenger RNA (mRNA) technology that’s enabled two of the safe and effective vaccines against COVID-19, which have been so instrumental in fighting the pandemic. This includes the latest boosters from both Pfizer and Moderna, which now offer updated protection against currently circulating Omicron variants.

While this isn’t the first attempt to develop a universal flu vaccine, past attempts had primarily focused on a limited number of conserved antigens. An antigen is a protein or other substance that produces an immune response. Conserved antigens are those that tend to stay the same over time.

Because conserved antigens will look similar in many different influenza viruses, the hope was that vaccines targeting a small number of them would afford some broad influenza protection. But the focus on a strategy involving few antigens was driven largely by practical limitations. Using traditional methods to produce vaccines by growing flu viruses in eggs and isolating proteins, it simply isn’t feasible to include more than about four targets.

That’s where recent advances in mRNA technology come in. What makes mRNA so nifty for vaccines is that all you need to know is the letters, or sequence, that encodes the genetic material of a virus, including the sequences that get translated into proteins.

A research team led by Scott Hensley, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, recognized that the ease of designing and manufacturing mRNA vaccines opened the door to an alternate approach to developing a universal flu vaccine. Rather than limiting themselves to a few antigens, the researchers could make an all-in-one influenza vaccine, encoding antigens from every known influenza virus subtype.

Influenza vaccines generally target portions of a plentiful protein on the viral surface known as hemagglutinin (H). In earlier work, Hensley’s team, in collaboration with Perelman’s mRNA vaccine pioneer Drew Weissman, showed they could use mRNA technology to produce vaccines with H antigens from single influenza viruses [2, 3]. To protect the fragile mRNA molecules that encode a selected H antigen, researchers deliver them to cells inside well-tolerated microscopic lipid shells, or nanoparticles. The same is true of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. In their earlier studies, the researchers found that when an mRNA vaccine aimed at one flu virus subtype was given to mice and ferrets in the lab, their cells made the encoded H antigen, eliciting protective antibodies.

In this latest study, they threw antigens from all 20 known flu viruses into the mix. This included H antigens from 18 known types of influenza A and two lineages of influenza B. The goal was to develop a vaccine that could teach the immune system to recognize and respond to any of them.

More study is needed, of course, but early indications are encouraging. The vaccine generated strong and broad antibody responses in animals. Importantly, it worked both in animals with no previous immunity to the flu and in those previously infected with flu viruses. That came as good news because past infections and resulting antibodies sometimes can interfere with the development of new antibodies against related viral subtypes.

In more good news, the researchers found that vaccinated mice and ferrets were protected against severe illness when later challenged with flu viruses. Those viruses included some that were closely matched to antigens in the vaccine, along with some that weren’t.

The findings offer proof-of-principle that mRNA vaccines containing a wide range of antigens can offer broad protection against influenza and likely other viruses as well, including the coronavirus strains responsible for COVID-19. The researchers report that they’re moving toward clinical trials in people, with the goal of beginning an early phase 1 trial in the coming year. The hope is that these developments—driven in part by technological advances and lessons learned over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic—will help to mitigate or perhaps even prevent future pandemics.

References:

[1] A multivalent nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine against all known influenza virus subtypes. Arevalo CP, Bolton MJ, Le Sage V, Ye N, Furey C, Muramatsu H, Alameh MG, Pardi N, Drapeau EM, Parkhouse K, Garretson T, Morris JS, Moncla LH, Tam YK, Fan SHY, Lakdawala SS, Weissman D, Hensley SE. Science. 2022 Nov 25;378(6622):899-904.

[2] Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination partially overcomes maternal antibody inhibition of de novo immune responses in mice. Willis E, Pardi N, Parkhouse K, Mui BL, Tam YK, Weissman D, Hensley SE. Sci Transl Med. 2020 Jan 8;12(525):eaav5701.

[3] Nucleoside-modified mRNA immunization elicits influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies. Pardi N, Parkhouse K, Kirkpatrick E, McMahon M, Zost SJ, Mui BL, Tam YK, Karikó K, Barbosa CJ, Madden TD, Hope MJ, Krammer F, Hensley SE, Weissman D. Nat Commun. 2018 Aug 22;9(1):3361.

Links:

Understanding Flu Viruses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

COVID Research (NIH)

Decades in the Making: mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines (NIH)

Video: mRNA Flu Vaccines: Preventing the Next Pandemic (Penn Medicine, Philadelphia)

Scott Hensley (Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Weissman Lab (Perelman School of Medicine)

Video: The Story Behind mRNA COVID Vaccines: Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman (Penn Medicine, Philadelphia)

NIH Support: National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Celebrating NIH Science, Blogs, and Blog Readers!

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Happy holidays to one and all! As you may have heard, this is my last holiday season as the Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—a post that I’ve held for the past 12 years and four months under three U.S. Presidents. And, wow, it really does seem like only yesterday that I started this blog!

At the blog’s outset, I said my goal was to “highlight new discoveries in biology and medicine that I think are game changers, noteworthy, or just plain cool.” More than 1,100 posts, 10 million unique visitors, and 13.7 million views later, I hope you’ll agree that goal has been achieved. I’ve also found blogging to be a whole lot of fun, as well as a great way to expand my own horizons and share a little of what I’ve learned about biomedical advances with people all across the nation and around the world.

So, as I sign off as NIH Director and return to my lab at NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), I want to thank everyone who’s ever visited this Blog—from high school students to people with health concerns, from biomedical researchers to policymakers. I hope that the evidence-based information that I’ve provided has helped and informed my readers in some small way.

In this my final post, I’m sharing a short video (see above) that highlights just a few of the blog’s many spectacular images, many of them produced by NIH-funded scientists during the course of their research. In the video, you’ll see a somewhat quirky collection of entries, but hopefully you will sense my enthusiasm for the potential of biomedical research to fight human disease and improve human health—from innovative immunotherapies for treating cancer to the gift of mRNA vaccines to combat a pandemic.

Over the years, I’ve blogged about many of the bold, new frontiers of biomedicine that are now being explored by research teams supported by NIH. Who would have imagined that, within the span of a dozen years, precision medicine would go from being an interesting idea to a driving force behind the largest-ever NIH cohort seeking to individualize the prevention and treatment of common disease? Or that today we’d be deep into investigations of precisely how the human brain works, as well as how human health may benefit from some of the trillions of microbes that call our bodies home?

My posts also delved into some of the amazing technological advances that are enabling breakthroughs across a wide range of scientific fields. These innovative technologies include powerful new ways of mapping the atomic structures of proteins, editing genetic material, and designing improved gene therapies.

So, what’s next for NIH? Let me assure you that NIH is in very steady hands as it heads into a bright horizon brimming with exceptional opportunities for biomedical research. Like you, I look forward to discoveries that will lead us even closer to the life-saving answers that we all want and need.

While we wait for the President to identify a new NIH director, Lawrence Tabak, who has been NIH’s Principal Deputy Director and my right arm for the last decade, will serve as Acting NIH Director. So, keep an eye out for his first post in early January!

As for me, I’ll probably take a little time to catch up on some much-needed sleep, do some reading and writing, and hopefully get out for a few more rides on my Harley with my wife Diane. But there’s plenty of work to do in my lab, where the focus is on type 2 diabetes and a rare disease of premature aging called Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. I’m excited to pursue those research opportunities and see where they lead.

In closing, I’d like to extend my sincere thanks to each of you for your interest in hearing from the NIH Director—and supporting NIH research—over the past 12 years. It’s been an incredible honor to serve you at the helm of this great agency that’s often called the National Institutes of Hope. And now, for one last time, Diane and I take great pleasure in sending you and your loved ones our most heartfelt wishes for Happy Holidays and a Healthy New Year!

mRNA Vaccines May Pack More Persistent Punch Against COVID-19 Than Thought

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Many people, including me, have experienced a sense of gratitude and relief after receiving the new COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. But all of us are also wondering how long the vaccines will remain protective against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19.

Earlier this year, clinical trials of the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines indicated that both immunizations appeared to protect for at least six months. Now, a study in the journal Nature provides some hopeful news that these mRNA vaccines may be protective even longer [1].

In the new study, researchers monitored key immune cells in the lymph nodes of a group of people who received both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine. The work consistently found hallmarks of a strong, persistent immune response against SARS-CoV-2 that could be protective for years to come.

Though more research is needed, the findings add evidence that people who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may not need an additional “booster” shot for quite some time, unless SARS-CoV-2 evolves into new forms, or variants, that can evade this vaccine-induced immunity. That’s why it remains so critical that more Americans get vaccinated not only to protect themselves and their loved ones, but to help stop the virus’s spread in their communities and thereby reduce its ability to mutate.

The new study was conducted by an NIH-supported research team led by Jackson Turner, Jane O’Halloran, Rachel Presti, and Ali Ellebedy at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. That work builds upon the group’s previous findings that people who survived COVID-19 had immune cells residing in their bone marrow for at least eight months after the infection that could recognize SARS-CoV-2 [2]. The researchers wanted to see if similar, persistent immunity existed in people who hadn’t come down with COVID-19 but who were immunized with an mRNA vaccine.

To find out, Ellebedy and team recruited 14 healthy adults who were scheduled to receive both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Three weeks after their first dose of vaccine, the volunteers underwent a lymph node biopsy, primarily from nodes in the armpit. Similar biopsies were repeated at four, five, seven, and 15 weeks after the first vaccine dose.

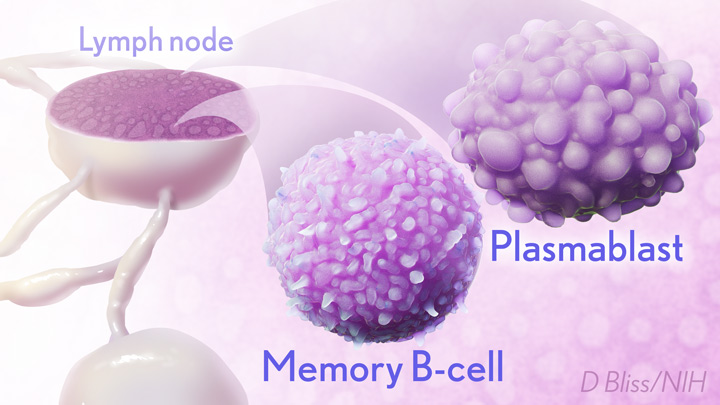

The lymph nodes are where the human immune system establishes so-called germinal centers, which function as “training camps” that teach immature immune cells to recognize new disease threats and attack them with acquired efficiency. In this case, the “threat” is the spike protein of SARS-COV-2 encoded by the vaccine.

By the 15-week mark, all of the participants sampled continued to have active germinal centers in their lymph nodes. These centers produced an army of cells trained to remember the spike protein, along with other types of cells, including antibody-producing plasmablasts, that were locked and loaded to neutralize this key protein. In fact, Ellebedy noted that even after the study ended at 15 weeks, he and his team continued to find no signs of germinal center activity slowing down in the lymph nodes of the vaccinated volunteers.

Ellebedy said the immune response observed in his team’s study appears so robust and persistent that he thinks that it could last for years. The researcher based his assessment on the fact that germinal center reactions that persist for several months or longer usually indicate an extremely vigorous immune response that culminates in the production of large numbers of long-lasting immune cells, called memory B cells. Some memory B cells can survive for years or even decades, which gives them the capacity to respond multiple times to the same infectious agent.

This study raises some really important issues for which we still don’t have complete answers: What is the most reliable correlate of immunity from COVID-19 vaccines? Are circulating spike protein antibodies (the easiest to measure) the best indicator? Do we need to know what’s happening in the lymph nodes? What about the T cells that are responsible for cell-mediated immunity?

If you follow the news, you may have seen a bit of a dust-up in the last week on this topic. Pfizer announced the need for a booster shot has become more apparent, based on serum antibodies. Meanwhile, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said such a conclusion would be premature, since vaccine protection looks really good right now, including for the delta variant that has all of us concerned.

We’ve still got a lot more to learn about the immunity generated by the mRNA vaccines. But this study—one of the first in humans to provide direct evidence of germinal center activity after mRNA vaccination—is a good place to continue the discussion.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Turner JS, O’Halloran JA, Kalaidina E, Kim W, Schmitz AJ, Zhou JQ, Lei T, Thapa M, Chen RE, Case JB, Amanat F, Rauseo AM, Haile A, Xie X, Klebert MK, Suessen T, Middleton WD, Shi PY, Krammer F, Teefey SA, Diamond MS, Presti RM, Ellebedy AH. Nature. 2021 Jun 28. [Online ahead of print]

[2] SARS-CoV-2 infection induces long-lived bone marrow plasma cells in humans. Turner JS, Kim W, Kalaidina E, Goss CW, Rauseo AM, Schmitz AJ, Hansen L, Haile A, Klebert MK, Pusic I, O’Halloran JA, Presti RM, Ellebedy AH. Nature. 2021 May 24. [Online ahead of print]

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Ellebedy Lab (Washington University, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

How Immunity Generated from COVID-19 Vaccines Differs from an Infection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A key issue as we move closer to ending the pandemic is determining more precisely how long people exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, will make neutralizing antibodies against this dangerous coronavirus. Finding the answer is also potentially complicated with new SARS-CoV-2 “variants of concern” appearing around the world that could find ways to evade acquired immunity, increasing the chances of new outbreaks.

Now, a new NIH-supported study shows that the answer to this question will vary based on how an individual’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were generated: over the course of a naturally acquired infection or from a COVID-19 vaccine. The new evidence shows that protective antibodies generated in response to an mRNA vaccine will target a broader range of SARS-CoV-2 variants carrying “single letter” changes in a key portion of their spike protein compared to antibodies acquired from an infection.

These results add to evidence that people with acquired immunity may have differing levels of protection to emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. More importantly, the data provide further documentation that those who’ve had and recovered from a COVID-19 infection still stand to benefit from getting vaccinated.

These latest findings come from Jesse Bloom, Allison Greaney, and their team at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. In an earlier study, this same team focused on the receptor binding domain (RBD), a key region of the spike protein that studs SARS-CoV-2’s outer surface. This RBD is especially important because the virus uses this part of its spike protein to anchor to another protein called ACE2 on human cells before infecting them. That makes RBD a prime target for both naturally acquired antibodies and those generated by vaccines. Using a method called deep mutational scanning, the Seattle group’s previous study mapped out all possible mutations in the RBD that would change the ability of the virus to bind ACE2 and/or for RBD-directed antibodies to strike their targets.

In their new study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Bloom, Greaney, and colleagues looked again to the thousands of possible RBD variants to understand how antibodies might be expected to hit their targets there [1]. This time, they wanted to explore any differences between RBD-directed antibodies based on how they were acquired.

Again, they turned to deep mutational scanning. First, they created libraries of all 3,800 possible RBD single amino acid mutants and exposed the libraries to samples taken from vaccinated individuals and unvaccinated individuals who’d been previously infected. All vaccinated individuals had received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine. This vaccine works by prompting a person’s cells to produce the spike protein, thereby launching an immune response and the production of antibodies.

By closely examining the results, the researchers uncovered important differences between acquired immunity in people who’d been vaccinated and unvaccinated people who’d been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, antibodies elicited by the mRNA vaccine were more focused to the RBD compared to antibodies elicited by an infection, which more often targeted other portions of the spike protein. Importantly, the vaccine-elicited antibodies targeted a broader range of places on the RBD than those elicited by natural infection.

These findings suggest that natural immunity and vaccine-generated immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will differ in how they recognize new viral variants. What’s more, antibodies acquired with the help of a vaccine may be more likely to target new SARS-CoV-2 variants potently, even when the variants carry new mutations in the RBD.

It’s not entirely clear why these differences in vaccine- and infection-elicited antibody responses exist. In both cases, RBD-directed antibodies are acquired from the immune system’s recognition and response to viral spike proteins. The Seattle team suggests these differences may arise because the vaccine presents the viral protein in slightly different conformations.

Also, it’s possible that mRNA delivery may change the way antigens are presented to the immune system, leading to differences in the antibodies that get produced. A third difference is that natural infection only exposes the body to the virus in the respiratory tract (unless the illness is very severe), while the vaccine is delivered to muscle, where the immune system may have an even better chance of seeing it and responding vigorously.

Whatever the underlying reasons turn out to be, it’s important to consider that humans are routinely infected and re-infected with other common coronaviruses, which are responsible for the common cold. It’s not at all unusual to catch a cold from seasonal coronaviruses year after year. That’s at least in part because those viruses tend to evolve to escape acquired immunity, much as SARS-CoV-2 is now in the process of doing.

The good news so far is that, unlike the situation for the common cold, we have now developed multiple COVID-19 vaccines. The evidence continues to suggest that acquired immunity from vaccines still offers substantial protection against the new variants now circulating around the globe.

The hope is that acquired immunity from the vaccines will indeed produce long-lasting protection against SARS-CoV-2 and bring an end to the pandemic. These new findings point encouragingly in that direction. They also serve as an important reminder to roll up your sleeve for the vaccine if you haven’t already done so, whether or not you’ve had COVID-19. Our best hope of winning this contest with the virus is to get as many people immunized now as possible. That will save lives, and reduce the likelihood of even more variants appearing that might evade protection from the current vaccines.

Reference:

[1] Antibodies elicited by mRNA-1273 vaccination bind more broadly to the receptor binding domain than do those from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Gentles LE, Crawford KHD, Starr TN, Malone KD, Chu HY, Bloom JD. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Jun 8.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Bloom Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Studies Confirm COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines Safe, Effective for Pregnant Women

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Clinical trials have shown that COVID-19 vaccines are remarkably effective in protecting those age 12 and up against infection by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The expectation was that they would work just as well to protect pregnant women. But because pregnant women were excluded from the initial clinical trials, hard data on their safety and efficacy in this important group has been limited.

So, I’m pleased to report results from two new studies showing that the two COVID-19 mRNA vaccines now available in the United States appear to be completely safe for pregnant women. The women had good responses to the vaccines, producing needed levels of neutralizing antibodies and immune cells known as memory T cells, which may offer more lasting protection. The research also indicates that the vaccines might offer protection to infants born to vaccinated mothers.

In one study, published in JAMA [1], an NIH-supported team led by Dan Barouch, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, wanted to learn whether vaccines would protect mother and baby. To find out, they enrolled 103 women, aged 18 to 45, who chose to get either the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccines from December 2020 through March 2021.

The sample included 30 pregnant women,16 women who were breastfeeding, and 57 women who were neither pregnant nor breastfeeding. Pregnant women in the study got their first dose of vaccine during any trimester, although most got their shots in the second or third trimester. Overall, the vaccine was well tolerated, although some women in each group developed a transient fever after the second vaccine dose, a common side effect in all groups that have been studied.

After vaccination, women in all groups produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, those antibodies neutralized SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. The researchers also found those antibodies in infant cord blood and breast milk, suggesting that they were passed on to afford some protection to infants early in life.

The other NIH-supported study, published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology, was conducted by a team led by Jeffery Goldstein, Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago [2]. To explore any possible safety concerns for pregnant women, the team took a first look for any negative effects of vaccination on the placenta, the vital organ that sustains the fetus during gestation.

The researchers detected no signs that the vaccines led to any unexpected damage to the placenta in this study, which included 84 women who received COVID-19 mRNA vaccines during pregnancy, most in the third trimester. As in the other study, the team found that vaccinated pregnant women showed a robust response to the vaccine, producing needed levels of neutralizing antibodies.

Overall, both studies show that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are safe and effective in pregnancy, with the potential to benefit both mother and baby. Pregnant women also are more likely than women who aren’t pregnant to become severely ill should they become infected with this devastating coronavirus [3]. While pregnant women are urged to consult with their obstetrician about vaccination, growing evidence suggests that the best way for women during pregnancy or while breastfeeding to protect themselves and their families against COVID-19 is to roll up their sleeves and get either one of the mRNA vaccines now authorized for emergency use.

References:

[1] Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in pregnant and lactating women. Collier AY, McMahan K, Yu J, Tostanoski LH, Aguayo R, Ansel J, Chandrashekar A, Patel S, Apraku Bondzie E, Sellers D, Barrett J, Sanborn O, Wan H, Chang A, Anioke T, Nkolola J, Bradshaw C, Jacob-Dolan C, Feldman J, Gebre M, Borducchi EN, Liu J, Schmidt AG, Suscovich T, Linde C, Alter G, Hacker MR, Barouch DH. JAMA. 2021 May 13.

[2] Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccination in pregnancy: Measures of immunity and placental histopathology. Shanes ED, Otero S, Mithal LB, Mupanomunda CA, Miller ES, Goldstein JA. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 May 11.

[3] COVID-19 vaccines while pregnant or breastfeeding. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Barouch Laboratory (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Jeffery Goldstein (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Next Page