progenitor cells

A Nose for Science

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Our nose does a lot more than take in oxygen, smell, and sometimes sniffle. This complex organ also helps us taste and, as many of us notice during spring allergy season when our noses get stuffy, it even provides some important anatomic features to enable us to speak clearly.

This colorful, almost psychedelic image shows the entire olfactory epithelium, or “smell center,” (green) inside the nasal cavity of a newborn mouse. The olfactory epithelium drapes over the interior walls of the nasal cavity and its curvy bony parts (red). Every cell in the nose contains DNA (blue).

The olfactory epithelium detects odorant molecules in the air, providing a sense of smell. In humans, the nose has about 400 types of scent receptors, and they can detect at least 1 trillion different odors [1].

But this is more than just a cool image captured by graduate student Lu Yang, who works with David Ornitz at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. The two discovered a new type of progenitor cell, called a FEP cell, that has the capacity to generate the entire smell center [2]. Progenitor cells are made by stem cells. But they are capable of multiplying and producing various cells of a particular lineage that serve as the workforce for specialized tissues, such as the olfactory epithelium.

Yang and Ornitz also discovered that the FEP cells crank out a molecule, called FGF20, that controls the growth of the bony parts in the nasal cavity. This seems to regulate the size of the olfactory system, which has fascinating implications for understanding how many mammals possess a keener sense of smell than humans.

But it turns out that FGF20 does a lot more than control smell. While working in Ornitz’s lab as a postdoc, Sung-Ho Huh, now an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, discovered that FGF20 helps form the cochlea [3]. This inner-ear region allows us to hear, and mice born without FGF20 are deaf. Other studies show that FGF20 is important for development of the kidney, teeth, mammary gland, and of specific types of hair [4-7]. Clearly, this indicates multi-tasking can be a key feature of a protein, not a trivial glitch.

The image was one of the winners in the 2018 BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition, sponsored by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB). Its vibrant colors help to show the basics of smell, and remind us that every scientific picture tells a story.

References:

[1] Humans can discriminate more than 1 trillion olfactory stimuli. Bushdid C1, Magnasco MO, Vosshall LB, Keller A. Science. 2014 Mar 21;343(6177):1370-1372.

[2] FGF20-Expressing, Wnt-Responsive Olfactory Epithelial Progenitors Regulate Underlying Turbinate Growth to Optimize Surface Area. Yang LM, Huh SH, Ornitz DM. Dev Cell. 2018;46(5):564-580.

[3] Differentiation of the lateral compartment of the cochlea requires a temporally restricted FGF20 signal. Huh SH, Jones J, Warchol ME, Ornitz DM. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(1):e1001231.

[4] FGF9 and FGF20 maintain the stemness of nephron progenitors in mice and man. Barak H, Huh SH, Chen S, Jeanpierre C, Martinovic J, Parisot M, Bole-Feysot C, Nitschke P, Salomon R, Antignac C, Ornitz DM, Kopan R. Dev. Cell. 2012;22(6):1191-1207

[5] Ectodysplasin target gene Fgf20 regulates mammary bud growth and ductal invasion and branching during puberty. Elo T, Lindfors PH, Lan Q, Voutilainen M, Trela E, Ohlsson C, Huh SH, Ornitz DM, Poutanen M, Howard BA, Mikkola ML. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5049

[6] Ectodysplasin regulates activator-inhibitor balance in murine tooth development through Fgf20 signaling. D Haara O, Harjunmaa E, Lindfors PH, Huh SH, Fliniaux I, Aberg T, Jernvall J, Ornitz DM, Mikkola ML, Thesleff I. Development. 2012;139(17):3189-3199.

[7] Fgf20 governs formation of primary and secondary dermal condensations in developing hair follicles. Huh SH, Närhi K, Lindfors PH, Häärä O, Yang L, Ornitz DM, Mikkola ML. Genes Dev. 2013;27(4):450-458.

Links:

Taste and Smell (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders/NIH)

Ornitz Lab, (Washington University, St. Louis)

Huh Lab, (University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha)

BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition, (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

These Oddball Cells May Explain How Influenza Leads to Asthma

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most people who get the flu bounce right back in a week or two. But, for others, the respiratory infection is the beginning of lasting asthma-like symptoms. Though I had a flu shot, I had a pretty bad respiratory illness last fall, and since that time I’ve had exercise-induced asthma that has occasionally required an inhaler for treatment. What’s going on? An NIH-funded team now has evidence from mouse studies that such long-term consequences stem in part from a surprising source: previously unknown lung cells closely resembling those found in taste buds.

The image above shows the lungs of a mouse after a severe case of H1N1 influenza infection, a common type of seasonal flu. Notice the oddball cells (green) known as solitary chemosensory cells (SCCs). Those little-known cells display the very same chemical-sensing surface proteins found on the tongue, where they allow us to sense bitterness. What makes these images so interesting is, prior to infection, the healthy mouse lungs had no SCCs.

SCCs, sometimes called “tuft cells” or “brush cells” or “type II taste receptor cells”, were first described in the 1920s when a scientist noticed unusual looking cells in the intestinal lining [1] Over the years, such cells turned up in the epithelial linings of many parts of the body, including the pancreas, gallbladder, and nasal passages. Only much more recently did scientists realize that those cells were all essentially the same cell type. Owing to their sensory abilities, these epithelial cells act as a kind of lookout for signs of infection or injury.

This latest work on SCCs, published recently in the American Journal of Physiology–Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, adds to this understanding. It comes from a research team led by Andrew Vaughan, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia [2].

As a post-doc, Vaughan and colleagues had discovered a new class of cells, called lineage-negative epithelial progenitors, that are involved in abnormal remodeling and regrowth of lung tissue after a serious respiratory infection [3]. Upon closer inspection, they noticed that the remodeling of lung tissue post-infection often was accompanied by sustained inflammation. What they didn’t know was why.

The team, including Noam Cohen of Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine and De’Broski Herbert, also of Penn Vet, noticed signs of an inflammatory immune response several weeks after an influenza infection. Such a response in other parts of the body is often associated with allergies and asthma. All were known to involve SCCs, and this begged the question: were SCCs also present in the lungs?

Further work showed not only were SCCs present in the lungs post-infection, they were interspersed across the tissue lining. When the researchers exposed the animals’ lungs to bitter compounds, the activated SCCs multiplied and triggered acute inflammation.

Vaughan’s team also found out something pretty cool. The SCCs arise from the very same lineage of epithelial progenitor cells that Vaughan had discovered as a post-doc. These progenitor cells produce cells involved in remodeling and repair of lung tissue after a serious lung infection.

Of course, mice aren’t people. The researchers now plan to look in human lung samples to confirm the presence of these cells following respiratory infections.

If confirmed, the new findings might help to explain why kids who acquire severe respiratory infections early in life are at greater risk of developing asthma. They suggest that treatments designed to control these SCCs might help to treat or perhaps even prevent lifelong respiratory problems. The hope is that ultimately it will help to keep more people breathing easier after a severe bout with the flu.

References:

[1] Closing in on a century-old mystery, scientists are figuring out what the body’s ‘tuft cells’ do. Leslie M. Science. 2019 Mar 28.

[2] Development of solitary chemosensory cells in the distal lung after severe influenza injury. Rane CK, Jackson SR, Pastore CF, Zhao G, Weiner AI, Patel NN, Herbert DR, Cohen NA, Vaughan AE. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019 Mar 25.

[3] Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Vaughan AE, Brumwell AN, Xi Y, Gotts JE, Brownfield DG, Treutlein B, Tan K, Tan V, Liu FC, Looney MR, Matthay MA, Rock JR, Chapman HA. Nature. 2015 Jan 29;517(7536):621-625.

Links:

Asthma (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Influenza (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Vaughan Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Cohen Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Herbert Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

The Science of Saliva

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

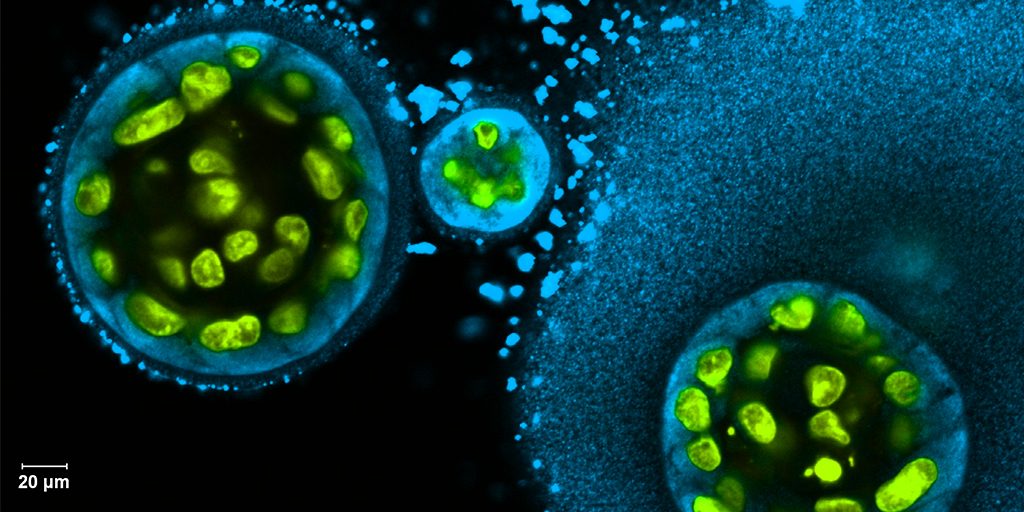

Credit: Swati Pradhan-Bhatt, Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE

Whether it’s salmon sizzling on the grill or pizza fresh from the oven, you probably have a favorite food that makes your mouth water. But what if your mouth couldn’t water—couldn’t make enough saliva? When salivary glands stop working and the mouth becomes dry, either from disease or as a side effect of medical treatment, the once-routine act of eating can become a major challenge.

To help such people, researchers are now trying to engineer replacement salivary glands. While the research is still in the early stages, this image captures a crucial first step in the process: generating 3D structures of saliva-secreting cells (yellow). When grown on a scaffold of biocompatible polymers infused with factors to encourage development, these cells cluster into spherical structures similar to those seen in salivary glands. And they don’t just look like salivary cells, they act like them, producing the distinctive enzyme in saliva, alpha amylase (blue).